How is it that one of the greatest two-way lineman in professional football history could barely make the opening kickoff of nearly every pro football game he ever played?

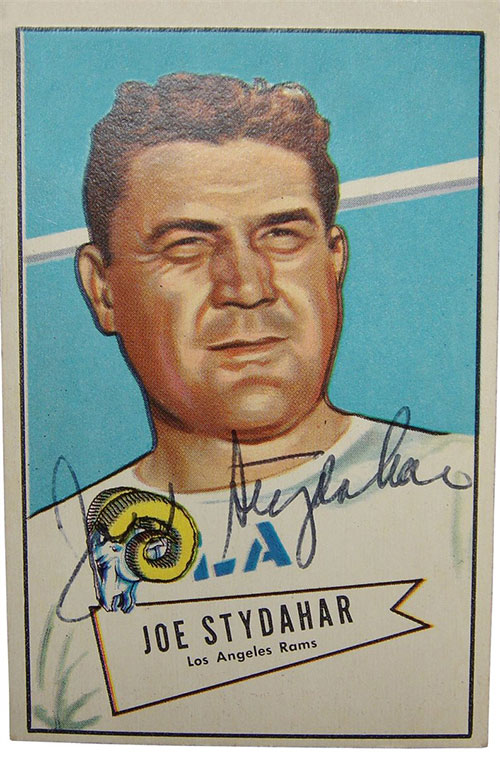

Joe Stydahar, the West Virginia University star and All-Pro player for George Halas’ dominant “Monsters of the Midway” Chicago Bears teams of the late 1930s and 1940s, was so nervous before games that he couldn’t play until he made a trip to the bathroom to relieve his nervous stomach.

His teammates called Joe’s stomach “Old Faithful” because they knew it was bound to erupt before each game. In fact, Stydahar rarely heard any of Halas’ final pregame instructions so the coach would often send one of his assistants in to see Joe to relay any last-minute messages he might have.

Once Joe was finished with his bathroom business, out he went to the field to dominate games like no other tackle during his time. Stydahar’s incessant worrying continued after his playing career ended when he became head coach of the Los Angeles Rams in the early 1950s. He once checked himself into a sanitarium following LA’s 1951 championship game victory over the Cleveland Browns where the examining physician there said he was suffering from “extreme mental tension.”

Stydahar may have had a bad case of the nerves, but he also had plenty of nerve on the playing field. A 60-minute man for Chicago, he was known for being one of the fiercest tacklers in the game. Following one game when his Rams team endured a bad loss to Philadelphia, Stydahar barked to his players, “No wonder you guys get kicked around. Every guy on this team has still got all of his teeth! When you charge you’ve got to keep your head up. You may lose a lot of teeth that way, but you also make a lot of tackles!”

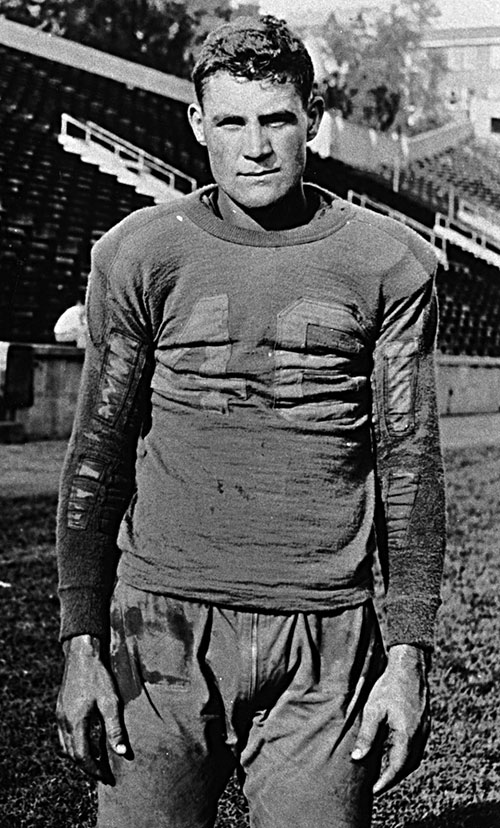

Stydahar’s journey to professional stardom began in Kaylor, Pennsylvania, where he was born March 16, 1912, to the son of a Yugoslavian coal miner. Joe’s family moved to Shinnston, West Virginia, when he was eight and Shinnston is the place he always called home.

Stydahar performed well enough at Shinnston High in football and basketball to get noticed by legendary Pitt coach Jock Sutherland, who oversaw one of the top college grid programs in the country in the early 1930s. Following a week of freshman workouts, however, Stydahar returned home to Shinnston for a weekend to visit his family. As the story goes, Stydahar was standing along a street corner waiting for his ride back to Pittsburgh when another car, driven by a West Virginia University supporter, pulled up alongside Big Joe and convinced him to take a ride through Morgantown on his way back to Pittsburgh.

Once Stydahar made it to Morgantown and he met with West Virginia coach Earle “Greasy” Neale (a well-earned nickname, by the way), Greasy “kidnapped” Stydahar by hiding him in a fraternity house until Pitt gave up looking for him.

The West Virginia University grid teams Stydahar played on in 1933, 1934 and 1935 experienced great difficulty winning more than it lost, through no fault of Stydahar’s, though. During his junior season, in 1934, Joe blocked a school-record seven punts, one of those coming against Duquesne that he returned for the game’s only score. The Dukes, then under the direction of highly successful coach Elmer Layden, had outstanding teams during that time, including capturing an Orange Bowl championship in 1936, and the Stydahar-led victory over the Dukes at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh was considered one of WVU’s best of that period.

In retrospect, Stydahar was probably more accomplished as a center on the Mountaineer basketball team where he led the team in scoring in 1934 with an average of 10.5 points per game and helped West Virginia to records of 14-5 in 1934 and 16-6 in 1935. Actually, Stydahar’s basketball jersey No. 44 is currently hanging from the rafters at the WVU Coliseum, although a guy named Jerry West was responsible for that happening, not for what Stydahar accomplished on the hardwood.

Nevertheless, despite the football team’s lack of success, Stydahar was named to the All-East team and also earned mention as an “unsung All-American,” leading to an invitation to play in the East-West Shrine Game in San Francisco and the College Football All-Star Game in Chicago.

Stydahar’s performance in the Chicago all-star game, along with a tip from Chicago Bears end Bill Karr, who played with Stydahar at West Virginia, led George Halas to make Stydahar Chicago’s surprise No. 1 choice in the first-ever pro football draft in 1936. Stydahar was the first lineman ever taken in the draft and he went ahead of such pro stalwarts as Russ Letlow, Tuffy Leemans and Joe Manaici that year.

Stydahar immediately rewarded Halas’s gamble by becoming the most dominant player in the league in 1937, earning more All-Pro votes that year than Washington Redskins ace passer Slingin’ Sammy Baugh. Stydahar, one of the biggest players in the league at that time standing 6-feet-4 inches and weighing almost 260 pounds, made the All-Pro team five straight years from 1937-41, helping the Bears to three pro titles during his nine-year professional career that was interrupted by two years of military service during World War II in 1943-44.

A year after Stydahar returned to the Bears following his two-year stint in the Navy, Halas asked Stydahar what he wanted to be paid for the 1946 season. “I’m all washed up,” Stydahar said. “Write in whatever you consider the right amount and I’ll sign it.”

Halas ended up paying Stydahar twice what he was making before Uncle Sam called him to service, a demonstration of the great appreciation Halas had for Stydahar’s contributions to the Chicago Bears organization. Stydahar helped Chicago to another championship that season, a 24-14 victory over the New York Giants, before retiring. That was the Bears’ final pro football title during the franchise’s dominant years and their last until 1963 when Stydahar was an assistant coach.

In 1947, Stydahar transitioned to coaching with the Los Angeles Rams, who owner Dan Reeves was slowly building into a pro football power by acquiring such star players as Tom Fears, Elroy Hirsch, Ollie Matson, Norm Van Brocklin and Bob Waterfield.

Stydahar’s Chicago teammate, Bob Snyder, coached the Rams at the time, but the franchise made a big leap forward when Snyder hired Clark Shaughnessy to run the offense. Eventually, Shaughnessy would replace Snyder as head coach in 1948, and Shaughnessy continued to guide the Rams toward the top of the league standings despite being disliked by nearly everyone in the organization. Eventually, Shaughnessy lost a power struggle with Reeves and was fired before the start of the 1950 season. Shaughnessy’s surprise replacement was offensive line coach Stydahar, who was about to become Gene Ronzani’s offensive line coach at Green Bay before Reeves named him Shaughnessy’s successor.

Shaughnessy, upon hearing that Stydahar was taking over the Rams, infamously remarked, “I could take any high school team in the country and beat them.”

What Stydahar lacked in game strategy he made up for in other areas, and he hired Bear teammate Hampton Pool to handle the Ram offense and defense while he oversaw the entire operation.

“Joe was a big, happy guy, a nice guy,” LA linebacker Don Paul recalled. “He was good with the press.”

Stydahar’s Ram teams were also good, winning nine games his first season in 1950 before losing, 30-28, to the Cleveland Browns on a last-minute Lou Groza field goal in the pro football championship game.

A year later, Stydahar led Los Angeles to an 8-4 record and a 24-17 victory over the Browns in the 1951 championship game when Stydahar brought quarterback Norm Van Brocklin off the bench in the second half and he fired a game-winning 73-yard touchdown pass.

But Stydahar, growing distrustful of Pool, issued an ultimatum to Reeves early in the 1952 season - “either Pool goes or I go.” After dropping the ’52 season opener to Cleveland, it was Stydahar who was issued his walking papers. Years later, Stydahar regretted putting himself in that situation.

“I used my pride instead of my mind,” he said. “I thought I was so big I couldn’t be replaced. Nobody’s that big - not in football, not in anything.”

Stydahar rebounded quickly and got a job coaching the Chicago Cardinals, but his two-year tenure with the Cardinals was a disaster, his Cardinal teams winning only three of 24 games with one tie. He was fired after the 1954 season.

Pat Summerall, who played for Stydahar in Chicago, once said of his coach, “He was the only person I knew who could smoke a cigar, chew tobacco and drink whiskey all at the same time.”

"I used my pride instead of my mind. I thought I was so big I couldn't be replaced. Nobody's that big - not in football, not in anything."

Joe Stydahar

Other than his brief two-year tenure as a Bears assistant coach in 1963-64, Stydahar’s career interests pushed him away from football. He worked for a container company in Chicago until his death in 1977 of a heart attack while on a business trip to Beckley, West Virginia.

“Joe was something special for me,” Halas said of his dear friend following his death. “Football fans know him as the first lineman drafted in the first round in 1936, as a true All-Pro, as a great football player, as one of the Bears’ all-time greats and as a Hall of Famer.

“But more important to any of the football accomplishments, Joe Stydahar was a man of outstanding character and loyalty … all things that made Joe a great football player were reflected in his successful business career.

Stydahar was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame in 1956 and inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1967. He also received the Sports Illustrated Silver Anniversary All-America Award in 1960 and was named to pro football’s 50th and 75th anniversary teams.

Stydahar was the first person with West Virginia University ties ever inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, and the second inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame.

During his Pro Football Hall of Fame induction ceremony speech, Stydahar concluded his remarks by acknowledging his treasured Mountain State heritage, “And lastly, I want to thank my wonderful family, relatives, brothers, sisters and friends from my dear state, West Virginia, who came here to help share this wonderful day. Thank you very kindly.”