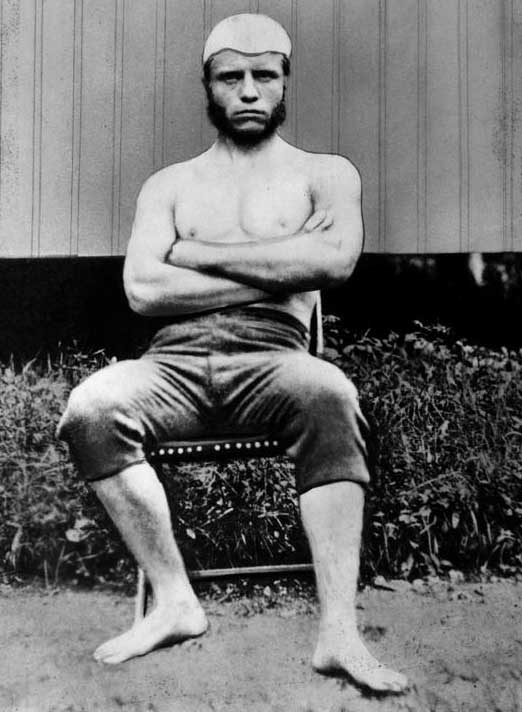

At the turn of the century, there was a serial killer on the loose preying on boys and young men and its name was college football. That’s right, college football, today the game so many of us have grown to love.

And while there have always been inherent risks playing such a physically demanding sport, college football at the turn of the century was far, far more savage and brutal than the form of the game we enjoy so much today.

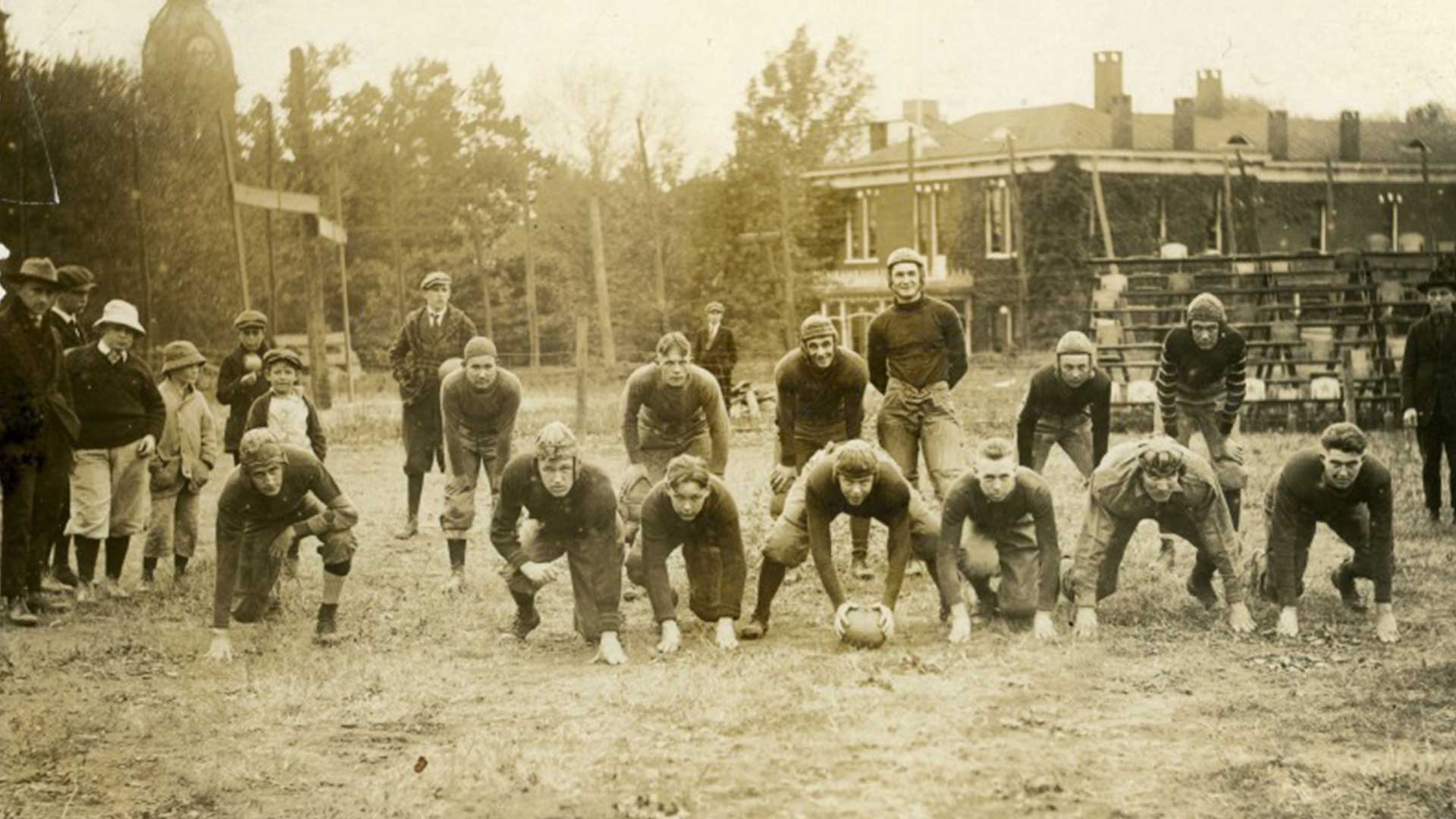

In those days, players had scant equipment, and those who did choose to stuff a little extra padding in their shirts or pants were frequently ridiculed by their teammates. The games were longer (70 minutes), there was hardly any substituting, no neutral zone to separate the offensive and defensive lines, forward passing was forbidden and five yards were all that were required to earn a first down.

Consequently, teams advanced the ball yard-by-yard, inch-by-inch, blow-by-blow, and, yes, sometimes punch-by-punch.

By 1905, football had grown so ugly and brutal that the nation’s leading newspapers annually tracked the deaths in the sport. The Chicago Tribune reported 18 deaths and 159 serious injuries could directly be attributed to football, increasing to 19, 20 or 21 deaths (opinions vary) in 1905 in what the Tribune called college football’s “death harvest.”

The growing number of fatalities caught the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt, a Harvard football fan and an enthusiastic supporter of “the strenuous life.” The former “Rough Rider” didn’t mind “a little manly interaction, so long as it is not fatal,” he once said.

But when Roosevelt’s son Theodore, Jr. was roughed up in Harvard’s freshman game against Yale (some believe deliberately) Roosevelt had had enough. He called the coaches of the nation’s three leading teams at the time - Harvard, Yale and Princeton - to the White House to encourage them to reduce the excessive physical play going on in games.

Several presidents at leading schools were threatening to disband their football teams, something Roosevelt was hoping to avoid, so what eventually came out of his conference with the coaches was the formation of an intercollegiate conference, the forerunner of the NCAA, in 1906, to implement significant rule changes to make the game much safer for the players.

Among the most significant revisions included the reduction of the length of the game from 70 to 60 minutes, establishment of a neutral zone the length of the ball separating both lines, an increase in the distance needed to earn a first down from five to 10 yards, prohibition of hurdling, the addition of another official to more closely observe illegal play at the line of scrimmage and the introduction of the forward pass.

These initial changes didn’t completely eliminate the inherent dangers of playing football, but deaths did decrease to 11 in 1906 and to 11 once again in 1907. Then, another spike in fatalities in 1909 required more reforms, most notably the loosening of restrictions on forward passing.

But still, players were dying. University of Chicago professor Shailer Mathews once called football “a boy killing, education prostituting, gladiatorial sport” and the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune one autumn published a cartoon depicting a Grim Reaper sitting on a goal post surveying the carnage on the football field below.

Football’s Grim Reaper eventually paid a visit to West Virginia University in 1910 when quarterback Rudolph Munk was killed while playing a football game against Bethany College at Island Stadium in Wheeling, West Virginia.

For those who knew Munk and observed his slight build and injury-prone nature, along with his insistence on continuing to play the game despite suffering a series of serious injuries, his fate was somewhat anticipated.

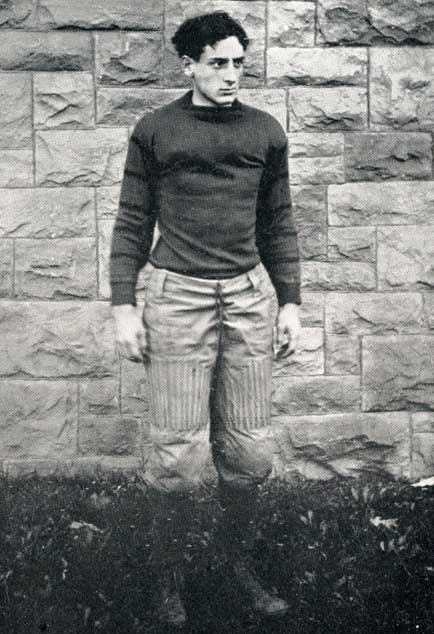

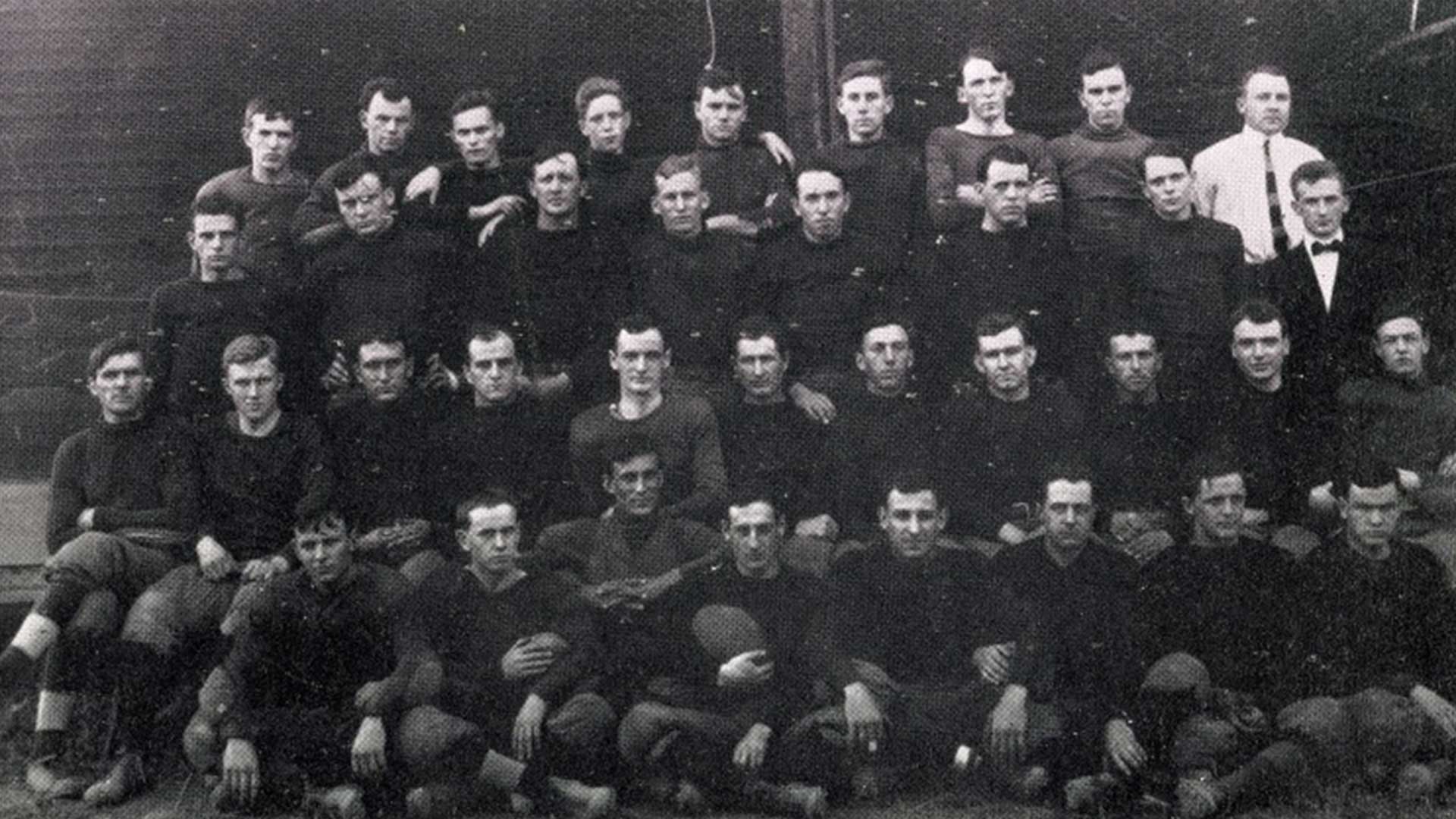

After graduating from Connellsville High in 1907, Munk played one season at Bucknell before transferring to WVU in 1909. Despite weighing just 130 pounds, Munk made the team as a quarterback and became one West Virginia’s top players, leading it in scoring with 36 points, 25 of those coming on five touchdown runs (touchdowns only counted for five points at that time).

He scored a pair of touchdowns in West Virginia’s 40-5 victory over Slippery Rock, and his 35-yard field goal in the final quarter was the deciding tally in West Virginia’s memorable 3-0 victory against Marietta in Parkersburg. Munk made three touchdown runs in West Virginia’s 49-0 victory over West Virginia Wesleyan, one of those, a 40-yarder in the second quarter, gave WVU a 16-0 lead.

But late in the Washington & Jefferson game to conclude the season, 3,000 fans watched in horror when Munk fell unconscious to the ground during a running play, his limp body sprawled out helplessly on the field. Doctors were summoned and he was carried to the gymnasium where stimulants were administered hypodermically to revive him. Rumors ran rampant around town that Munk was deliberately punched in the back of the head by a Washington & Jefferson player, but no one on the field witnessed such an act.

Munk, unconscious for two days, eventually recovered, although he frequently suffered from “dizzy spells, spots before the eyes and other symptoms,” according one of his attending physicians. Nevertheless, nine months later he was in the starting lineup for West Virginia’s 6-0 victory over Westminster to open the 1910 season, but the quarterback was once again injured during West Virginia’s 38-0 loss at Penn, requiring him to miss the team’s next two games against Bethany and Bucknell.

Munk returned to the field for WVU’s game against Marietta, a 10-6 loss in which he was responsible for both scores by kicking two fourth-quarter field goals. He also played in a 38-0 loss to Pittsburgh at Forbes Field, making one long run on a trick play that nearly went for a score. The following week, a rematch with Bethany billed in the Wheeling newspapers as the “state championship of West Virginia” was scheduled for Saturday, November 12 at Island Stadium. The prior game against The Bisons in Morgantown ended in a 0-0 tie, and West Virginia Wesleyan, which lost to a Waynesburg team West Virginia defeated 41-0, was eliminated from contention, meaning the West Virginia-Bethany winner would own state football bragging rights.

The game was hard-fought and “plucky,” according to news accounts, continuing that way even after West Virginia took a first-half lead on James Thompson’s 20-yard touchdown run. Early in the fourth quarter, Munk tacked on a 15-yard dropkick for a field goal to give West Virginia a more comfortable 8-0 lead.

After exchanging possessions, West Virginia took a Bethany punt at the 40 and began marching toward their goal line. Runs by Thompson and halfback Ernest Bell moved the football to the Bethany 30-yard line where Munk was struck in the head by Bison player Ernie McCoy (later found out to be Canton, Ohio resident Thomas McCoy, a ringer) and collapsed to the ground, McCoy falling on top of him. When the play ended, McCoy got up, looked down at the motionless Munk laying on the ground and walked away, according to later court testimony.

Umpire Homer C. Young immediately ejected McCoy, who walked off the field without protesting. Teammates came to Munk’s aid and team physician Dr. O.M. Staats tended to him until an ambulance could be summoned. Munk was transported to a local hospital where he died three hours later. The game resumed for a few more plays until it was called off with two minutes still remaining and the ball resting on the Bethany 18-yard line. No one on the field was interested in continuing the game.

Immediately, the city coroner and prosecuting attorney made inquiries into the circumstances surrounding Munk’s death. Testimony was taken from players and coaches from both teams, and also from Young, the official who ejected McCoy. Young’s Sunday morning statement to the coroner indicated that he believed McCoy’s intent was to put Munk out of the game. The official said he had warned McCoy on a prior play that if his rough tactics didn’t cease he would be thrown out. On the fatal play, Young said he observed McCoy break through the line and “follow Munk for about 10 yards behind the line of scrimmage” before striking him, according to the Wheeling Intelligencer’s Monday morning account of the game.

From this testimony, the prosecuting attorney issued a warrant for McCoy’s arrest. Two days later, after conflicting testimony from players, coaches and officials attending the game - including Young recanting his initial Sunday morning version by stating that he was not positive McCoy’s actions were intentional - a coroner’s jury refused to implicate McCoy of any criminal responsibility in the death of Munk.

The verdict of the coroner’s jury, published in the New York Times, read, “We do say that the evidence of this case is conflicting, and therefore we believe that Rudolph Munk came to his death on Nov. 12 by colliding with Thomas McCoy in a game of football played in Ohio County, West Virginia.”

Munk was buried a few days later in his hometown of Connellsville, and West Virginia’s three remaining games scheduled that season against West Virginia Wesleyan, Dickinson and Washington & Jefferson were cancelled.

Several rival teams, including Pitt coach Joseph H. Thompson, issued statements following Munk’s death, “While we regret such things, it cannot influence the game one way or another. Munk should have never been allowed to play in the game at all. I was afraid when West Virginia played us a week ago that something of the kind would happen. Munk, while a fine fellow, a good student and a good football player, was a man of small physique and weak in the lungs. He was not the kind of man to play football at all.”

Football at WVU resumed in 1911 with a full nine-game slate under fourth-year coach Charles Augustus Leuder, who steered the team to a 6-3 record that season.

A plaque reading “In Memory of Rudolph Munk, 1889-1910, captain football team 1910, fatally injured in Bethany game, Nov. 12, 1910 at Wheeling, W.Va.” was placed at old Mountaineer Field and was later relocated to new Mountaineer Field in 1991 as part of the school’s centennial celebration.

Munk remains the only West Virginia University athlete to die while playing a football game, although Cassell “Ike” Mowrey was struck in the head while playing a baseball game against Pitt in Morgantown in 1923. He died a few days later in a local hospital.

It was two very sad tragedies, separated by 13 years, that left a permanent impression on those who knew them during a time when playing college sports was a very real life-and-death proposition.