A fiery, young, coach whose innovative offensive system based on speed and precision elevates Mountaineer football to unprecedented heights before abruptly resigning for greener pastures in the Big Ten Conference … sounds a lot like Rich Rodriguez, doesn’t it?

Well, this is actually the depiction of coach Clarence Spears’s four-year association with West Virginia University football from 1921-24 - a true Golden Era in Mountaineer athletics.

Those alive to witness Spears’s powerhouse Mountaineer teams operate in the mid-1920s maintain that he was the greatest football coach in school history and was destined to permanently put West Virginia University football on the national map had he remained in Morgantown.

He was that good and his WVU teams were that good.

But the combustible Spears could never seem to stay in one place for too long, first leaving his alma mater, Dartmouth, after four seasons for a bigger paycheck at West Virginia, then leaving WVU after four years for a bigger paycheck at Minnesota, then departing Minnesota after five years for a couple of autumns out in Oregon before circling the wagons and returning to the Midwest to coach at Wisconsin.

Spears lasted four years in Madison before wearing out his welcome and getting the ax in 1936 after a very public spat with athletic director Dr. Walter E. Meanwell. Three days after Spears’s firing at Wisconsin, Toledo, looking for a “name” coach to ignite its sagging football program, and, ignoring Spears’s messy divorce with the Badgers, immediately jumped at the chance to hire a coach with his pedigree.

Spears’s seven seasons at Toledo led to one more shot at the big time as Clark Shaughnessy’s replacement at Maryland. But in College Park, the aging coach fizzled out after only two seasons and his 27-year career in college football was finished.

Spears experienced moderate success at Minnesota - his third Golden Gopher club led by All-American fullback Bronko Nagurski capturing a share of the Big Ten title in 1927 and his Minnesota teams winning 28 of 40 games with three ties.

And Spears’s two-year tenure at Oregon was also considered successful with a 13-4-2 overall record, but at all of his subsequent coaching stops he was never able to match what he accomplished during those three fantastic years he had at West Virginia University in 1922, 1923 and 1924.

Those three Mountaineer teams, plus the squad Spears handed assistant coach Ira Errett Rodgers in 1925, were as good as any football teams in America.

Only once before, in 1919, when coach Mont McIntire had Rodgers, did West Virginia have anything close to the material Spears was putting out on the field during the mid-1920s. McIntire’s 11 in 1919 had impressive victories over Princeton, Rutgers and Washington & Jefferson, but the Mountaineers failed to defeat the two strongest teams on their schedule that year - Pitt and tiny Centre College from Danville, Kentucky – and ended the season with a somewhat disappointing 8-2 record.

McIntire’s 1917 team also teased West Virginia fans with a great 7-0 triumph at Navy - the first victory of national significance for WVU in 26 years of playing football, but the Mountaineers followed up that great win with a tie against Rutgers, a mysterious loss to West Virginia Wesleyan in battle for state supremacy, as well as a 6-2 defeat to Dartmouth and its first-year coach Clarence Spears, leaving the record at a coulda-shoulda-woulda 6-3-1.

Fan frustration with McIntire reached its apex in 1920 when West Virginia limped through another underachieving season, winning the games it was supposed to and losing or tying the other games fans felt McIntire’s team should have won. McIntire bowed out after the ’20 season, prompting athletic director Harry Stansbury to go shopping for a “name” coach to get the football program over the hump.

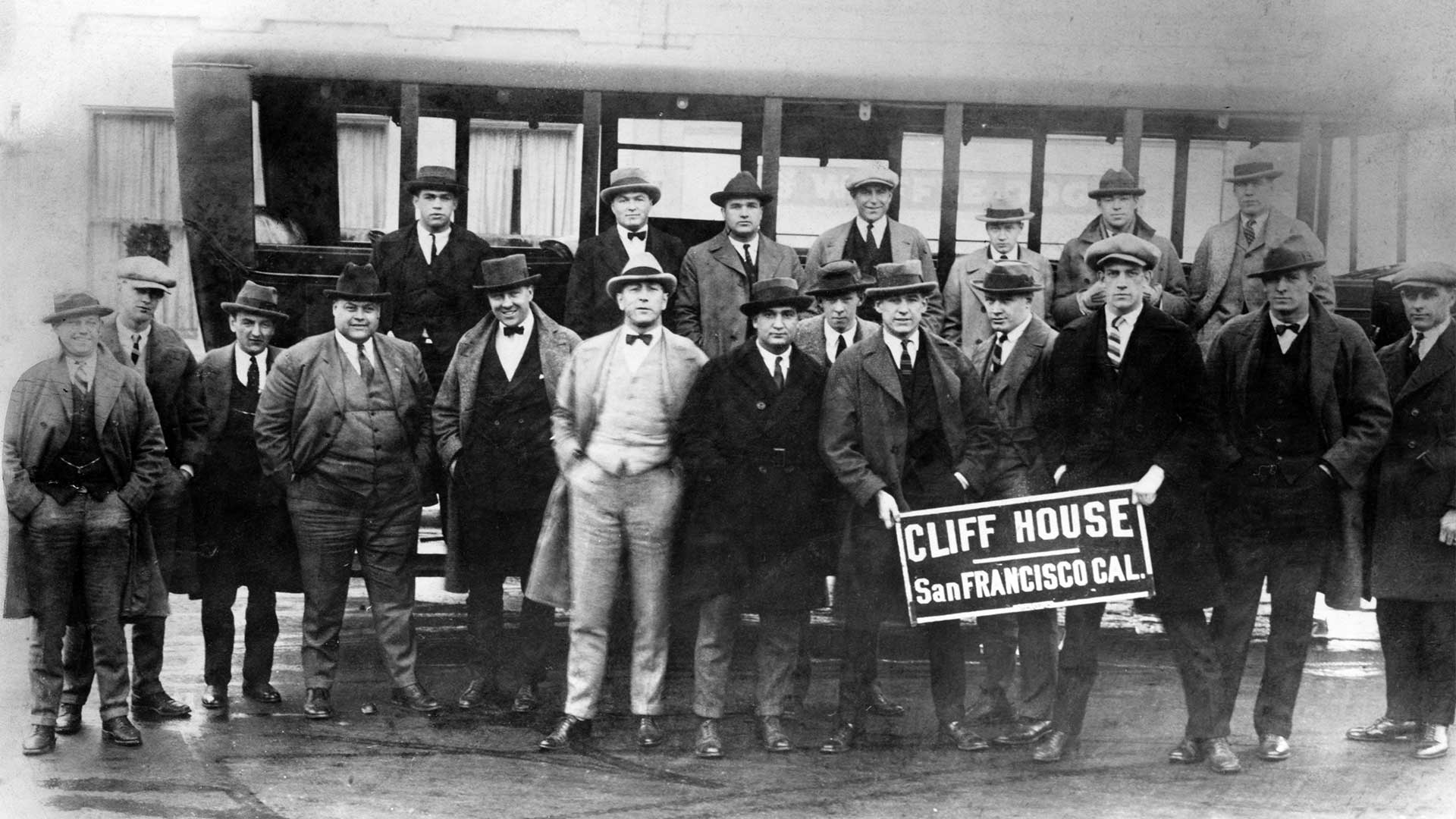

Stansbury first set his sights on Cornell’s Gil Dobie, but details couldn’t be worked out, so he sifted through the letters he received for the football coaching vacancy and pulled out the one written by Spears, who was looking for a ticket out of Hanover, New Hampshire. The two met in Chicago during the December 1920 NCAA meetings and came to an agreement on the WVU job.

In Spears, Stansbury was getting a 26-year-old football coach considered to be one of the top young strategists in the game who led Dartmouth to a 6-1-1 record in 1919 and a 7-2 record in 1920. He was also getting a crafty, self-made man who, in addition to being a great football coach, had financed his medical schooling at Dartmouth by working odd jobs.

At West Virginia, Spears would supplement his coaching income by opening a medical practice, something he attempted to continue at the other places he coached.

Highest Winning Percentage for Muliple Season Coaches

| Name | Years | Record |

|---|---|---|

| Clarence "Doc" Spears | 1921-24 | 30-6-3 (.808) |

| Bill Stewart | 2007-10 | 28-12 (.700) |

| Rich Rodriguez | 2001-07 | 60-26 (.698) |

| Carl Forkum | 1905-06 | 13-6 (.684) |

| Mont M. McIntire | 1916-17, 19-20 | 24-11-4 (.667) |

| Jim Carlen | 1966-69 | 25-13-3 (.646) |

| Sol Metzger | 1914-15 | 10-6-1 (.618) |

| Bobby Bowden | 1970-75 | 42-26 (.618) |

| Don Nehlen | 1980-00 | 149-93-4 (.614) |

| Art "Pappy" Lewis | 1950-59 | 58-38-2 (.602) |

A promising first season in 1921 saw Spears’s Mountaineers win five of 10 games with one tie, including competitive losses to Pitt, Rutgers and Greasy Neale’s undefeated Washington & Jefferson team that tied California in the Rose Bowl.

In 1922, with more pieces in place, Spears led West Virginia to a 10-0-1 record, the only blemish being a 12-12 tie to Washington & Lee in Charleston when he chose to let others coach the team while he scouted the following week’s opponent Rutgers, a rare oversight he never duplicated.

West Virginia upset Pitt in Pittsburgh when freshman Armin Mahrt, one of Spears’s Ohio discoveries, drop-kicked a field goal late in the game to defeat the Panthers. Born out of this great triumph was the phrase “West By Gawd Virginia” uttered by a slightly overserved Mountaineer fan who had noticed Spears and his players returning to the William Penn Hotel after the game.

Following the tie with Washington & Lee, the Spearsmen didn’t allow another touchdown for the remainder of the regular season - shutout victories over Rutgers, Cincinnati, Indiana, Virginia, Ohio and the finale before more than 13,000 fans against rival Washington & Jefferson at “Splinter Stadium,” located where the current Mountainlair plaza now sits.

Spears’s juggernaut rolled up 19 first downs and 315 total yards, compared to only seven first downs and 132 total yards for the Presidents in a 14-0 victory. A mere 26 days prior, Washington & Jefferson came back from 13 points down at halftime against Jock Sutherland’s Lafayette team to defeat the Maroons, 14-13, before more than 50,000 fans at the Polo Grounds in New York City.

The win over W&J led to an invitation to play Gonzaga in the San Diego East-West Christmas Classic, later simply referred to as the East-West Bowl. Spears’s Mountaineers didn’t disappoint in their first-ever postseason appearance, defeating Gonzaga 21-13 at San Diego’s Balboa Stadium.

At that moment, West Virginia football had reached the big time under Clarence Spears.

In 1923, West Virginia was invited to play Penn State at Yankee Stadium on October 27, the game ending in a 13-13 tie, and the following weekend the Mountaineers made a return trip to the Big Apple to face Rutgers at the Polo Grounds, a 27-7 West Virginia win.

The big victory that season was a 13-7 decision over Pop Warner’s Pitt Panthers before nearly 30,000 at Forbes Field. Spears’s Mountaineers thoroughly dominated the game, West Virginia outgaining the Panthers 309-54 and holding Pitt to only three first downs. It was the last time for 30 years West Virginia beat Pitt in consecutive seasons.

However, West Virginia’s aspirations of earning a Rose Bowl bid were buried in ankle-deep mud when Washington & Jefferson upset the Mountaineers, 7-2, before nearly 18,000 stunned home fans. Representing the East instead of West Virginia in the Rose Bowl was 6-2-1 Penn State, which needed a Harry Wilson touchdown run late in the fourth quarter to tie the Mountaineers in New York City.

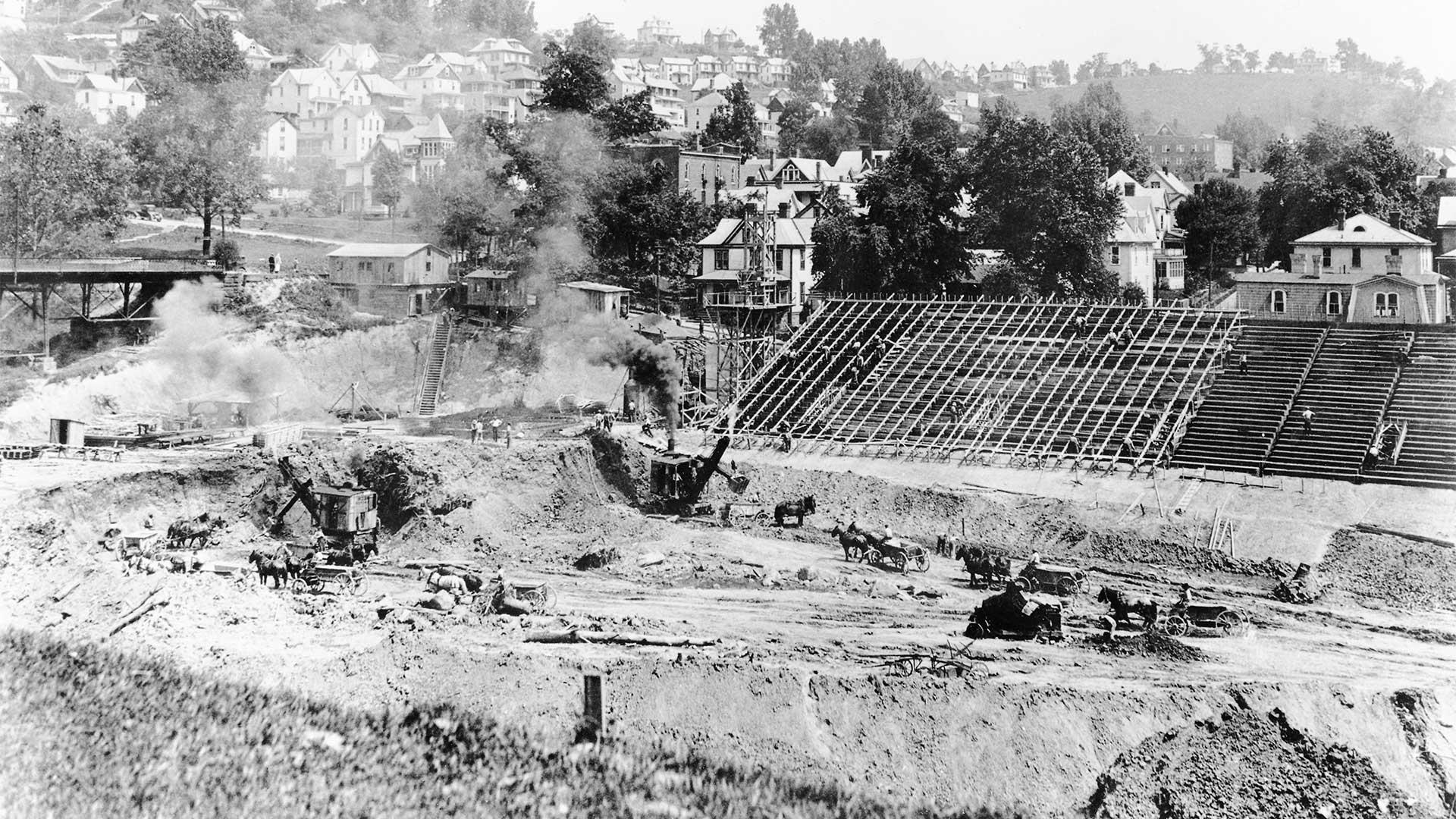

By this time, interest in WVU football had reached the point to where Stansbury needed to build a new football stadium to accommodate all of the fans that were showing up to watch Spears’s teams play.

Stansbury hoped to make a substantial dent in the funding for a new stadium by seeking donations during the Washington & Jefferson game, but the Mountaineers’ disappointing performance and the quagmire conditions left many hand-written contributions illegible, which led to less than half of what Stansbury had hoped to raise.

Undeterred, Stansbury pressed on with his new stadium project despite not having all of the funding in place. His decision to build Mountaineer Field would have far-reaching consequences for the athletic department when the football program fell on hard times following Spears’s departure in the mid-1920s and well into the 1930s when the Great Depression besieged the country.

Nevertheless, Spears again fielded another terrific squad in 1924 (probably the best of his four teams at West Virginia), the lone blemish being a 14-7 loss to a Pitt team coached for the first time by Jock Sutherland.

WVU was invited back to the Polo Grounds for a rematch against Centre College, a 13-6 West Virginia victory, and the Mountaineers gained revenge of Washington & Jefferson by totally throttling the Presidents 40-7 in one of the worst beatings in W&J history. The Spearsmen played like tigers that afternoon in piling up 18 first downs and 330 yards of offense in perhaps the most dominating performance of his WVU tenure.

Once again in 1924, West Virginia came up a little short of reaching the big game in Pasadena, California, though, this time the Rose Bowl choosing 5-1-1 Navy instead of WVU.

Spears Year-by-Year

| Season | W-L-T | Pct. |

|---|---|---|

| 1921 | 5-4-1 | .550 |

| 1922 | 10-0-1 | .955 |

| 1923 | 7-1-1 | .833 |

| 1924 | 8-1-0 | .889 |

Key Results by Spears

| Date | Opponent | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 10/14/22 | at Pitt | W, 9-6 |

| 11/30/22 | Washington & Jefferson | W, 14-0 |

| 12/25/22 | vs. Gonzaga | W, 21-13 |

| 10/13/23 | at Pitt | W, 13-7 |

| 10/27/23 | vs. Penn State | T, 13-13 |

| 11/6/23 | vs. Rutgers | W, 27-7 |

| 10/25/24 | vs. Centre College | W, 13-6 |

| 11/27/24 | Washington & Jefferson | W, 40-7 |

From 1922-24, Spears’s Mountaineers won 25 games, lost just two, with two ties for an .897 winning percentage. William Boand, who in 1930 developed the Azzi Ratem system used by Illustrated Football and the Football News during the 1930s and 1940s, retroactively analyzed the college football seasons from 1919 through 1929 and determined that Spears’s final three WVU teams were among the seven best in college football during their respective seasons, including the 1924 team Boand rated fourth in the country.

Spears was the first WVU football coach to really go beyond state borders to attract star players, procuring such talent as Mahrt from Dayton, Ohio, running back Nick Nardacci from Youngstown, Ohio, backs Gus Ekberg and Gordon McMillan from Minneapolis, quarterback Phil Pfleger from Chicago, halfback Woody Bruder from Houston, halfback Luther Titley from Denver, fullback Ed Morrison from Erie, Pennsylvania, and fullback Mike Hardy from Sharon, Pennsylvania.

Despite having another strong team returning in 1925, and a new 30,000-seat football stadium to showcase the squad in, Spears was growing restless in Morgantown. He knew Stansbury was struggling to come up with the funding to offset the rising costs of the new stadium, plus, Stansbury was now preoccupied with a big fight to keep West Virginia University out of the West Virginia Conference.

In an effort to rein in Stansbury’s growing WVU athletic department, fueled by Spears’s enormous success on the gridiron, George M. Ford, state superintendent of schools and a member of West Virginia’s first football team in 1891, wanted to morph West Virginia University into a more streamlined state school system and have athletics compete in the West Virginia Conference with the smaller colleges in the state. Ford likely saw Spears’s profitable Mountaineer football program as a means to help finance some of the state’s financially struggling smaller institutions, and probably enhance his personal standing among them as well.

Stansbury rightfully argued that by doing so would be a great blow to West Virginia University’s prestige and would ruin the school’s standing in the East. Ultimately, Stansbury won the fight to keep WVU out of the West Virginia Conference, but in the process he lost his football coach.

Spears chose to become Minnesota’s football coach in the summer of 1925 in a protracted negotiating process that spilled out into the newspapers. Spears’s final decision to accept Minnesota’s offer culminated a hectic week of conferences and negotiations, conflicting statements, rumors, suspense and daily reports that left West Virginians in a daze. At one point, Spears indicated his desire to return to WVU for a fifth season in 1925 but a sudden turn in the course of negotiations led him to change his mind and accept Minnesota’s offer.

Immediately, assistant coach and popular star Mountaineer player Ira Errett Rodgers was tabbed Spears’s replacement. Following a successful season in 1925 with Spears’s handpicked players, Rodgers’ teams began to decline each year until he ultimately resigned under pressure following the 1930 season.

For several years afterward, when West Virginia was considering new football coaches, there was always a large faction of Clarence Spears supporters who wanted WVU to bring him back to Morgantown, once the outcry growing so great it required Spears to make a public statement declining his interest in returning to the Mountain State.

“I wish to correct the impression that I am looking for the job,” he said. “I am perfectly satisfied here at Wisconsin and probably will be here as long as they will have me. While I still have a very warm spot in my heart for West Virginia and have many friends there, I wish you would state definitely that there is no possibility of my returning.”

It would take West Virginia University more than 40 years after Clarence Spears’s death in 1964 before the Mountaineers approached the consistent success they enjoyed during those Golden years of 1922, 1923 and 1924 on the gridiron.

And as irony would have it, the architect of those great WVU teams of 2005, 2006 and 2007, Rich Rodriguez, chose to depart for the greener pastures of the Big Ten Conference in a similar fashion and under much similar circumstances as Clarence Spears did in the mid-1920s, demonstrating once again how history can frequently repeat itself.

WVU Hall of Fame Members Coached by Spears

| Name | Season | Year Inducted |

|---|---|---|

| Fred Graham | 1921-25 | 2009 |

| Joseph Harrick | 1917-21 | 2011 |

| Walter "Red" Mahan | 1922-25 | 1999 |

| Homer Martin | 1919-22 | 1995 |

| Ross McHenry | 1924-26 | 2000 |

| Russ Meredith | 1917, 20-22 | 2001 |

| Fred "Jack" Simons | 1920-23 | 2007 |

"I wish to correct the impression that I am looking for the job. I am perfectly satisfied here at Wisconsin and probably will be here as long as they will have me. While I still have a very warm spot in my heart for West Virginia and have many friends there, I wish you would state definitely that there is no possibility of my returning."

Clarence Spears

Spears Career as Head Coach

| Years | School |

|---|---|

| 1917-20 | Dartmouth |

| 1921-24 | West Virginia |

| 1925-29 | Minnesota |

| 1930-31 | Oregon |

| 1932-35 | Wisconsin |

| 1936-42 | Toledo |

| 1943-44 | Maryland |