Believe it or not, there was actually a time when Pitt, Penn State, West Virginia and Syracuse all got along.

At least briefly.

It happened in the spring of 1962 when the four major Eastern schools reached an agreement to outlaw the practice of redshirting in all sports, and it was five years in the making.

There were some exceptions, of course, including significant injuries, military service or religious commitments, but redshirting an athlete simply for athletic developmental purposes was strictly forbidden by the four institutions who were growing wary of an overemphasis on intercollegiate sports, namely, college football.

It was a time of unprecedented collegiality among the four schools, and, specifically, among the school’s four athletic directors at the time - Frank Carver (Pitt), Ernie McCoy (Penn State), Red Brown (West Virginia) and Lew Andreas (Syracuse).

The sanguine Carver was particularly instrumental in cultivating harmonious relations between Pitt’s three main athletic rivals. His willingness to cooperate with the Mountaineers, Nittany Lions and Orangemen in the early 1960s eventually drew Pitt supporters into two conflicting camps - those who viewed Carver as an Anwar Sadat and those who viewed him as a Neville Chamberlain.

“Carver was series and rivalry minded,” the late Eddie Barrett, West Virginia’s noted sports information director, once recalled. “He abhorred the over-ambitious Pitt program.”

By the early 1960s, Pitt’s football program was a mere shadow of what it once was in the 1930s when Jock Sutherland’s Panthers were one of college football’s most dominant programs. By the late 1930s, however, Sutherland’s football locomotive was about to run off the tracks. Pitt chose to de-emphasize its grid program when some Panther players threatened to go on strike because of the school’s failure to follow through on some of Sutherland’s promises to them, and eventually, after Sutherland’s abrupt resignation, Pitt’s grid fortunes took a deep nose dive.

As the school’s publicity director, Carver was a first-hand witness to Pitt’s trying times in the late 1930s and he never forgot West Virginia’s willingness to cooperate with the Panthers when other schools wouldn’t.

“I remember the late 1930s, when every school was taking potshots at us,” Carver once recalled in 1965. “But West Virginia never said a word. They stuck by us and I will never forget that.”

In the mid-1960s, with Carver now running Pitt’s athletic department, Panther football was once again in crisis mode. After a nine-win season in 1963, Pitt sank to just three wins in 1964, and then to single-win seasons in 1966, 1967 and 1968.

Pitt was annually facing one of the toughest grid slates in the country with intersectional games against the likes of Oregon, USC, UCLA, Cal, Notre Dame, Illinois, Wisconsin and Oklahoma. Compounding matters, Pitt presidents Edward Litchfield and Wesley Posvar had a somewhat different outlook on intercollegiate athletics.

“Carver was a realist,” Barrett recalled. “Pitt was being run by Litchfield and Posvar and they were trying to make Pitt like an Ivy League school requiring things like two years of foreign language when, hell, English was a foreign language to many of their players.”

In the meantime, the redshirting agreement of 1962 between the four schools had developed into an informal relationship a few years later that became known as the “Big Four.” Soon, other issues such as scholarship limitations, roster sizes, scheduling and officiating were being regulated through the Big Four agreement.

According to Leland Byrd, former West Virginia University director of athletics, the Big Four was always viewed favorably by WVU and Syracuse.

“Syracuse and ourselves, we really felt it helped us because it limited the number of scholarships Pitt and Penn State could give out,” he said. “It really helped with our recruiting - at least we thought so - because Pitt and Penn State could only take so many (prospects) and that left the other players available for us to recruit in Pennsylvania at that particular time.”

As for Penn State, the Nittany Lions viewed the Big Four with indifference because they were dominating Eastern recruiting at the time and were able to plug any remaining holes in their roster with walk-ons.

“It didn’t affect Penn State either way because they had so many walk-ons and they didn’t need the (extra) scholarships at that point,” Byrd said. “Penn State was in between - they weren’t for or against it.”

As for Pitt, the Panthers grew to hate the Big Four as their football fortunes continued to sink in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

During a nine-year period from 1964-71, Pitt’s football records were 3-5-2, 3-7, 1-9, 1-9, 1-9, 4-6, 5-5, 3-8 and 1-10 before the Panthers finally pulled the plug on Carl DePasqua, Pitt’s third football coach during a seven-year period.

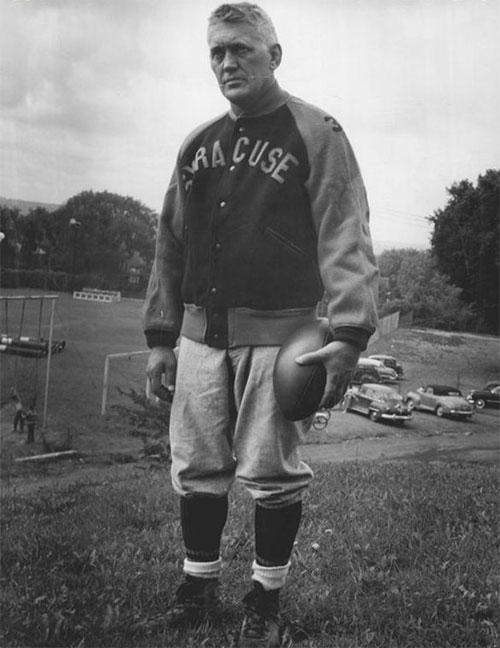

Meanwhile, Joe Paterno had turned Penn State into an Eastern football superpower rivaling some of Sutherland’s greatest Pitt teams of the mid-1930s, Syracuse had one of the stronger grid programs in the country in the late 1950s and early 1960s under Ben Schwartzwalder with an impressive array of talent including running backs Jim Brown, Ernie Davis, Jim Nance, Floyd Little and Larry Csonka, not to mention a pretty fair tight end named John Mackey, before Orange football fell on hard times in the early 1970s when Schwartzwalder began to age.

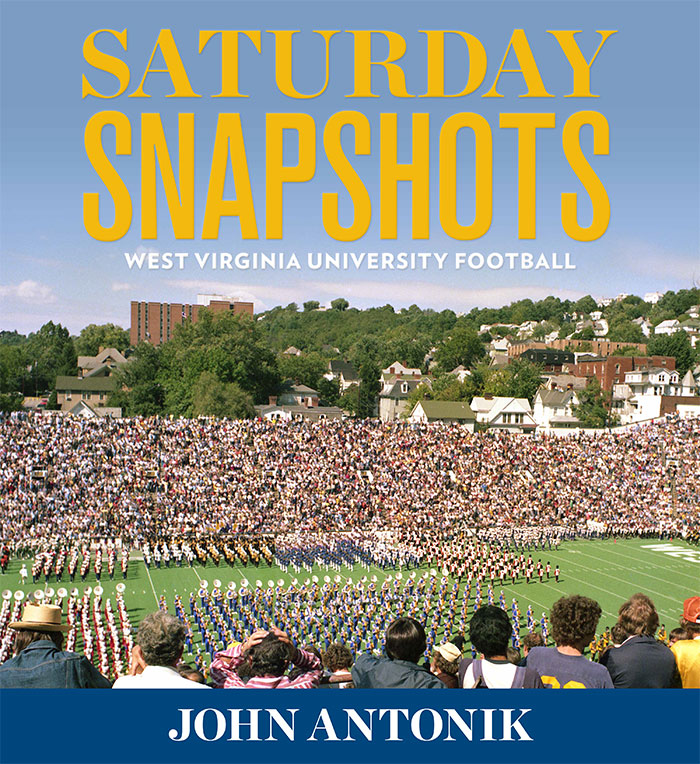

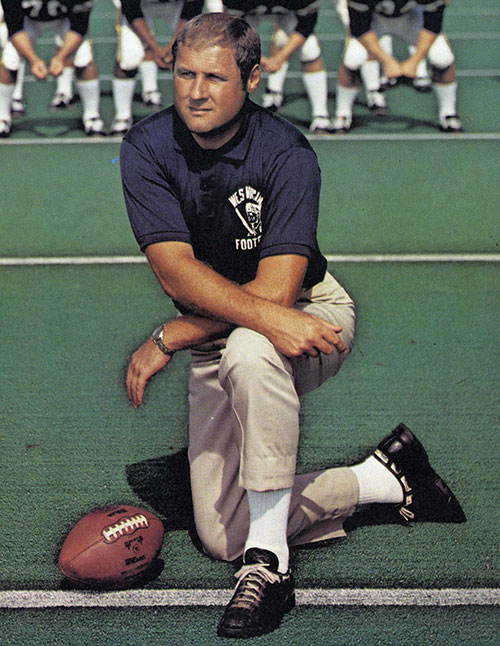

West Virginia, too, experienced moderate success in the 1960s, the Mountaineers going to a bowl game in 1964 and undergoing a resurgence in the late 1960s when Jim Carlen’s improvements to the WVU program began to take hold.

Naturally, Pitt was concerned about Schwartzwalder’s success at Syracuse and his great run of players, and West Virginia’s improving program under Carlen was also worrisome, but the Panthers were downright envious of what Paterno was doing at Penn State.

The gap between the two schools had grown to the point where Penn State was regularly beating Pitt by 30 points or more, including a 65-9 Penn State victory in 1968 and a 55-18 Nittany Lion beating in 1971.

And Pitt blamed the Big Four for nearly all of its football woes.

According to a 1972 editorial in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette by sportswriter Marino Parascenzo, Pitt’s football program was suffering the most from the Big Four agreement.

“The records suggest that if the Big Four arrangement wasn’t totally responsible, it had an erosive effect, at the least,” Parascenzo wrote. “Penn State, Pitt’s principal rival for Western Pennsylvania talent, improved on an already impressive record. From 1962 through 1971, the Lions went 9-1, 7-3, 6-4, 5-5, 8-2, 10-0, 10-0, 7-3 and 11-1.

“Perhaps, by coincidence, the Lions also have had five of their 10 bowl visits in that span, and perhaps, in reverse of the erosive effects at Pitt, four of them have come since 1967.

“Of the other two Big Four members, West Virginia has improved and Syracuse has declined, and whether the Big Four has been a factor in either case is a debatable point.”

Parascenzo added, “In recruiting -- and for a wide variety of reasons -- Pitt has been wedged out by its Big Four agreement. Syracuse is the lone power in New York, West Virginia in West Virginia. And Penn State exercises territorial rights to almost the entire East. (Syracuse coach Ben Schwartzwalder, for example, has said that he has beaten Penn State on only one of the last 25 players each school has sought).”

There were also whispers from the other three schools that the crafty, self-protective Paterno was skirting the Big Four agreement in subtle ways, such as traveling more players to road games than was permissible. It was a regular occurrence for sportswriters to take out their binoculars to count the number of Penn State players standing on the opposing sideline during games with the Nittany Lions in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

West Virginia, too, was accused of skirting the agreement with its decision to retroactively redshirt quarterback Bernie Galiffa for the 1969 season. The school cited “residual back pains” during Galiffa’s sophomore year and his sitting out that season was a “period of rehabilitation.” Pitt viewed that explanation with a fair level of suspicion, particularly in 1971 and 1972 when Galiffa’s back was healthy enough to lead West Virginia to a pair of blowout victories over the Panthers.

Paterno, too, was growing wary of Big Four. One, because he wasn’t sure the other schools were following the agreement to the letter and, two, because he was never a big fan of Penn State being associated with West Virginia University in the first place.

According to Penn State professor emeritus Ronald A. Smith, in his new book Wounded Lions: Joe Paterno, Jerry Sandusky and the Crises in Penn State Athletics, Paterno’s true colors shone during one Nittany Lion Club meeting that included Penn State president John Oswald.

Oswald had addressed the group first by touting the school’s support of the Big Four agreement and the cooperative spirit the four participating schools had achieved since its inception. Paterno then followed Oswald’s remarks by deriding the Big Four, explaining that Penn State should not be “comparing itself to an institution like West Virginia, but should have higher national aspirations.”

Therefore, by the summer of 1972, the air of collegiality and cooperation between Eastern football’s four major athletic programs was nearing its end. The first stone was cast when Pitt pulled out of the Big Four.

“I wasn’t surprised because we could see it coming,” Byrd said. “I talked to Red Brown about it when I took the West Virginia job (in the summer of 1972) and Red was very much in favor of the Big Four agreement but the problem was Pitt was already beginning to get around some of the Big Four stipulations and we were concerned about that.”

In announcing the school’s decision to pull out of the Big Four, Pitt athletic director Cas Myslinski summed up his school’s position thusly, “We’ve taken control of our football fortune away from the hands of three other schools,” he stated.

A couple months later, Myslinski fired DePasqua and hired Iowa State coach Johnny Majors, who immediately instituted a southern approach to Pitt’s football program by signing massive recruiting classes in 1972 and 1973 that eventually led to the Panthers’ ascension to the top of the national polls in 1976.

“Carver refused to go to a game after Johnny Majors became the Pitt coach,” Barrett once recalled.

Among the players signed in Majors’ first Pitt recruiting class, which numbered 70 or 80 players depending upon who you asked, was Hopewell High running back Tony Dorsett - a player Joe Paterno wanted very badly.

The more Pitt challenged Penn State for top Eastern recruits, the more Pitt-Penn State relations continued to deteriorate.

Ironically, what Majors did at Pitt in the mid-1970s leading to the Panthers’ national championship in 1976 was exactly what Jim Carlen wanted to do at West Virginia before leaving for Texas Tech following the Mountaineers’ Peach Bowl victory over South Carolina in 1969.

“Georgia Tech, where I had been, was an engineering school,” the late Carlen recalled in 2009. “We could take very few players that were marginal (academically), and Coach (Bobby) Dodd and Coach (Paul) Bryant were inseparable, but the biggest argument they ever had was over scholarships.

“(Dodd) said, ‘Paul, I want you to get your pencil out because I want you to put these numbers down. You’re signing 55 players a year and I’m signing 32 players a year, on average. Then, you redshirt your eight to 10 players - so you’re signing your 55 and we’re signing our 32 and we’re never over the total of 120 (players) and we’re on the cusp all the time. You start writing those numbers down and tell me what the difference is going to be. We’re bringing in our 32 to your 55 and this has got to stop!’”

Carlen continued.

“So when I would go to talk to Mr. Brown he would say, ‘You can’t do that.’ I said, ‘Mr. Brown, I know you are a basketball man and everything but we’re in a different world here now. These people need something to grab ahold of and Marshall is not going to be it. You’ve got to help me a little bit. I want to get out of the Southern Conference (by the mid-1960s West Virginia was only playing a handful of football games a year against Southern Conference opponents anyway) because we’re better than that. I want to play Kentucky and Tennessee and I want to play in bowl games.”

For Carlen, that meant signing big recruiting classes like Alabama was doing and spending more money to build up the Mountaineer football program. These issues came to a head in the fall of 1969 when Carlen asked the school to submit a modification to the Big Four agreement stipulating a relaxation of the strict redshirt requirements and roster limitations instituted in 1962. When this happened, the three other schools balked, threatening to drop West Virginia from its football schedules if Carlen was allowed to follow through with his plan.

Ultimately, Carlen’s solution to his dilemma was to take the Red Raiders job.

“Red did mention that Carlen wanted to do that but Red kind of squashed that because he said, ‘Hey, we don’t have the manpower to do that and we’re better off staying where we are,’” Byrd said.

Nevertheless, what came out of Pitt’s decision to pull out of the Big Four in 1972 was a growing disenchantment that eventually led to the splintering of the four schools two decades later when Penn State left the East entirely for the Big Ten Conference.

Today, Pitt and Syracuse are members of the Atlantic Coast Conference, Penn State remains in the Big Ten and West Virginia University is now a member of the Big 12 Conference.

Asked at his first ACC media day last year about being part of the Pitt-Syracuse football rivalry, Panther coach Pat Narduzzi cracked, “It is a rivalry? I guess it’s a rivalry.”

Narduzzi grew up 70 miles from Pittsburgh and regularly watched the Panthers play West Virginia and Penn State on the gridiron. West Virginia and Pitt haven’t played since 2011. West Virginia and Penn State last played in 1992, and Pitt and Penn State’s last met in 2000.

“(The dissolution of the Big Four) probably was the start (of the disintegration in cooperation) because Penn State never really got over the fact that Pitt violated the agreement and they had to change their ideas about recruiting as well,” Byrd said. “After that point, Pitt and Penn State could never seem to agree on anything. It was amazing that we were able to get them together on the Eastern Eight, but of course, that just involved basketball at that particular time and it didn’t have anything to do with football.”

Today, the Northeast is now made up of the ACC, the Big Ten, and, since 2012, the Big 12 - something unimaginable back in the early 1960s when the Big Four was emblematic of the unprecedented spirit of cooperation that once existed between Pitt, Penn State, Syracuse and West Virginia.

“I don’t think Penn State has benefitted (athletically) from (the move to the Big Ten),” Byrd said. “I think they were better off dominating the East than just being an also-ran in the Big Ten. Same thing with Pitt. I don’t think the ACC has helped them (performance-wise). This scattering of the schools really hasn’t helped any of the Eastern schools. Penn State, Pitt, Syracuse, Boston College, West Virginia, Rutgers, and then possibly Maryland and Virginia Tech, that would have been one hell of a conference.

“But,” Byrd sighed, “money speaks.”

Indeed, it does.