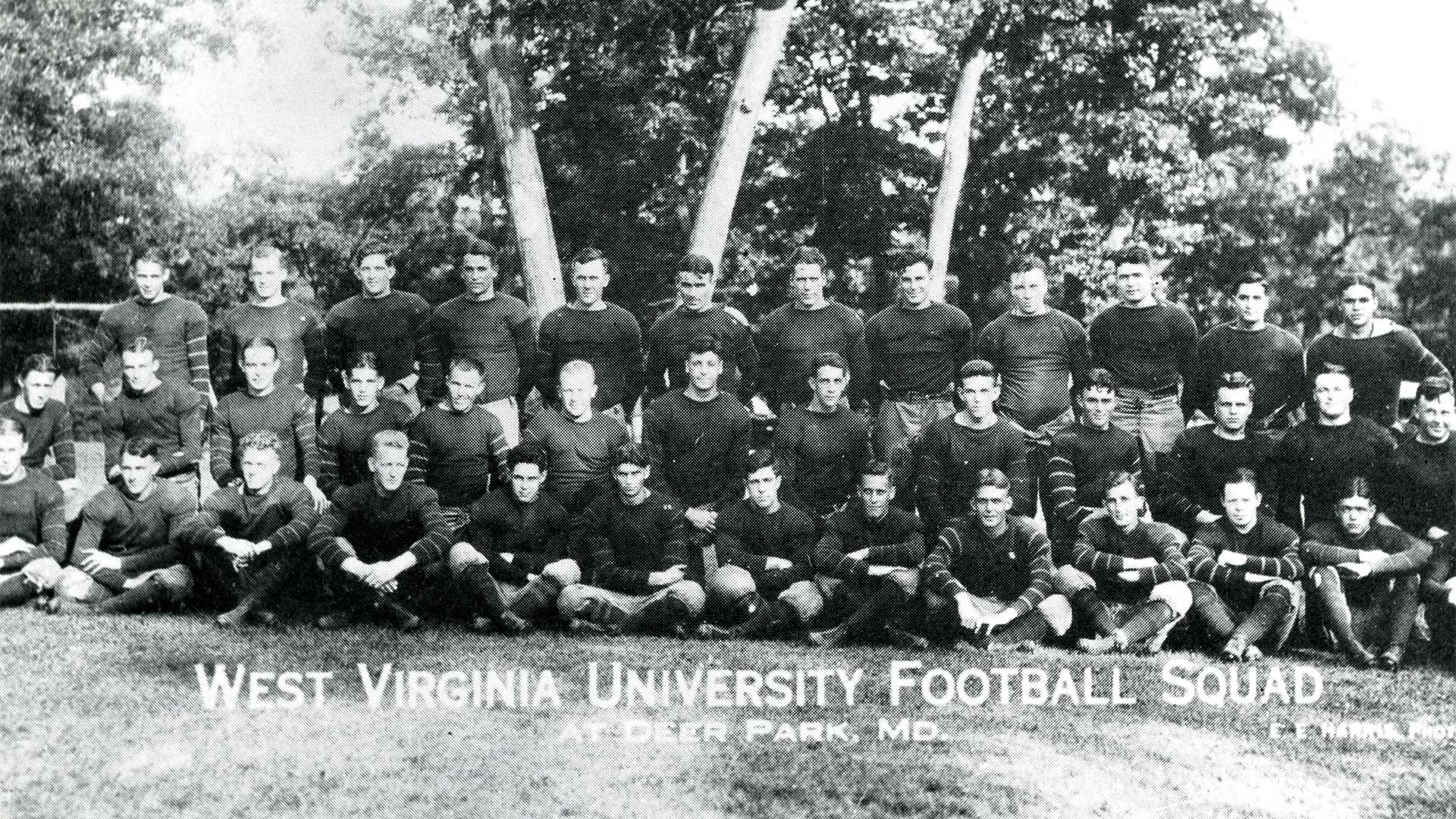

By my count, the West Virginia University Sports Hall of Fame presently has 68 Mountaineer football players and coaches enshrined among the school’s all-time athletic immortals.

Considering WVU has been playing football now for 125 years, to the casual fan, that number may seem far too low for the substantial number of great players, coaches and administrators who have been involved with Mountaineer football through the years.

And it is until you realize that the WVU Sports Hall of Fame has been playing catch-up ever since its late establishment in 1991 on the recommendation of former West Virginia University track and field and cross country coach Dr. Martin Pushkin.

It was Pushkin who finally got the ball rolling at WVU after attending Virginia Tech’s enshrinement ceremonies in 1990 to introduce one of his former Hokie athletes, track star Jerry Gaines, into the Hokie Hall of Fame.

Consequently, because of such a late undertaking, those serving on the Hall of Fame selection committee have done a yeoman’s job through the years making up for lost time.

The vast majority of the most deserving Mountaineer football players are either in the WVU Sports Hall of Fame or are in the queue to be inducted when they become eligible. Such unforgettable names as Avon Cobourne, Willie Drewrey, Dennis Fowlkes, Todd Sauerbrun, Renaldo Turnbull, John Thornton and Ron Wolfley have already been up for discussion, soon to be joined by a new crop of terrific candidates that will include quarterback Pat White, running backs Steve Slaton and Owen Schmitt and All-American center Dan Mozes, to name just a few, from Rich Rodriguez’s great Mountaineer teams of a decade ago. Soon, Bill Stewart and Dana Holgorsen’s greatest players will be up for discussion as well.

Most of the time periods are well-represented with enshrinees: one from the pre-1920s (the incomparable Ira Errett Rodgers), nine from the 1920s, five from the 1930s, four from the 1940s, 13 from the 1950s, 12 from the 1960s, six from the 1970s, nine from the 1980s and eight from the 1990s.

The new millennials are now getting representation, too, with the induction of 2003 consensus All-America linebacker Grant Wiley this fall.

Naturally, West Virginia’s three strongest decades of football excellence - the 1920s, 1950s and 1980s - have the largest number of representatives, 31 out of 68, so far. That is to be expected. When the time comes for those from the 2000s to be considered, that era’s number will swell, too.

However, as time marches on, memories fade and committee members begin transitioning to the Great Hall of Fame Above, there are some very deserving Mountaineer greats through the years who have slipped through the cracks for one reason or another. Had the WVU Sports Hall of Fame been in place in the 1950s or 1960s, many more Mountaineer grid greats would have received their just due.

At any rate, here are seven terrific Pre-World War II West Virginia University football players deserving of hall of fame recognition, but will likely never attain that status as attentions now shift toward the school’s deserving crop of contemporary candidates:

1. Lewis Oscar “Bull” Smith (HB) 1900-02

Before Ira Errett Rodgers came on the scene in 1915, Bull Smith was THE standard for Mountaineer ball carriers. Born in Tyler County, in 1880, Smith attended West Liberty Normal School in West Liberty, West Virginia, before finding his way to WVU in 1900 as a law student.

Smith scored at least 13 rushing touchdowns in 1902 (West Virginia scored 14 touchdowns that were unaccounted for in a 78-0 victory over West Virginia Wesleyan that season) and many of those came from long distances. He scored four TDs in West Virginia’s 53-0 victory over Grove City College, made four long touchdown runs in the Mountaineers’ 25-6 win over Westminster, one of those a 70-yard kickoff return for a score, and he produced one of West Virginia’s four touchdowns in the Mountaineers’ big, 23-5 win over Western University of Pittsburgh, now known as the Pitt Panthers.

But it was his performance against Washington & Jefferson in 1903, a year after his departure from West Virginia University, that forever etched his name into Mountaineer football lore.

In eight prior meetings against the Presidents - WVU’s Public Enemy No. 1 back then - the Mountaineers had scored a grand total of ZERO points, compared to W&J’s 256, which averages out to 32-0 beatings per year for the Old Gold and Blue.

Desperate to reverse this trend, West Virginia convinced Smith, by then coaching football at West Virginia Wesleyan, to re-enroll at WVU late in the fall semester to suit up one more time for the Mountaineers as a “ringer.” Smith agreed, and his first-half, 20-yard touchdown run, which included a nifty hurdle over a W&J defender at the line of scrimmage, gave WVU its first-ever lead against the Presidents.

And Smith’s touchdown stood up until the waning moments of the game when West Virginia, with the ball near Washington & Jefferson’s goal line, was poised to push the ball across to put the game on ice. That’s where President players continuously kicked the ball away as the referee placed the ball down to be snapped, eventually requiring him to rule the game a forfeit victory for the Mountaineers.

History records the game as a 6-0 West Virginia victory, meaning Smith’s fabulous touchdown dash was for naught in the record books. Also lost to history was the massive brawl that ensued, the West Virginia players and the two officials having to fight their way to the train station to get out of town. Later that evening, a massive celebration took place on campus and classes were canceled the following Monday as celebrating spilled over into the following week.

By the way, Smith was also a tremendous outfielder on the baseball diamond who appeared in 13 Major League games during three short stints with Pittsburgh in 1904, with Chicago in 1906 and Washington in 1911.

Smith died in 1928 at age 48.

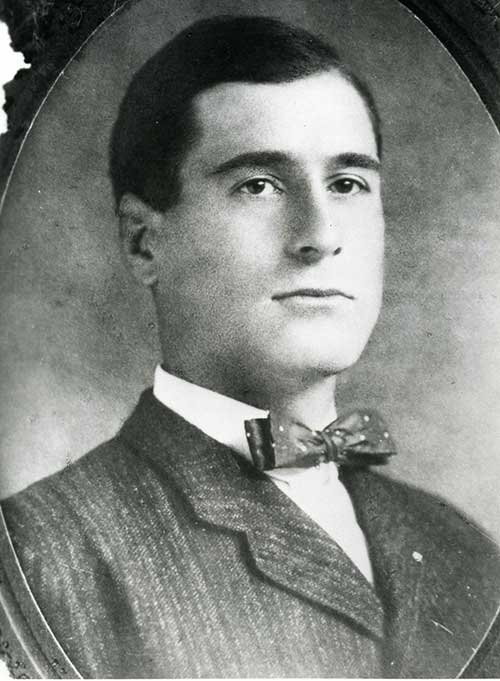

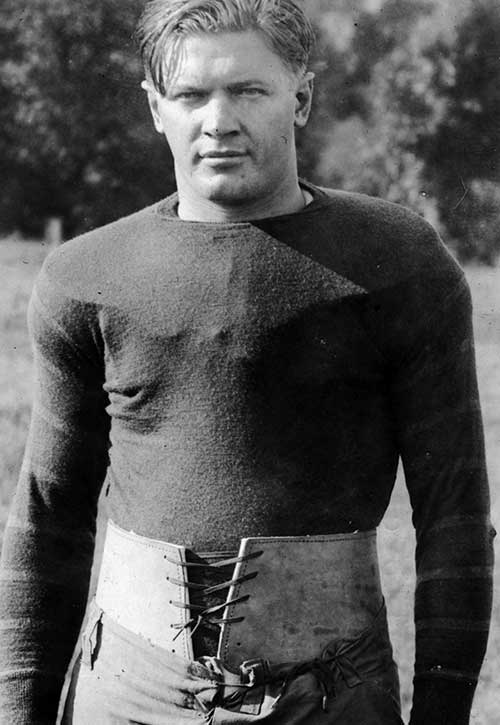

2. Clay Hite (HB) 1914-19

In the early teens, West Virginia’s new football coach, Sol Metzger, began mining the state’s high schools and prep schools in search of the best homegrown talent he could find. Among Metzger’s Mountain State discoveries were the school’s first All-American players, Ira Errett Rodgers and Russ Bailey. In fact, Metzger stocked West Virginia’s cupboard so fully with outstanding players that Pennsboro’s Paddy Lambert had to go to Michigan for playing time, where he earned All-America honors in 1917.

Included among Metzger’s outstanding West Virginia’s discoveries was speedy Huntington halfback Clay Hite, who became Rodgers’ No. 1 pass catching target on the great 1919 Mountaineer team that defeated Princeton and finished the season with an 8-2 record. Hite caught an inordinately high number of aerials that season - 15 for 286 yards and two touchdowns - including a 45-yard scoring pass from Rodgers in West Virginia’s big, 30-7 victory over Rutgers.

Against the Scarlet Knights, Hite was the recipient of West Virginia’s “lay out play,” which required him to sneak off to the side of the field and lay down flat on his back right before the ball was snapped. Then, when the ball was put in play, he would jump up and run down the field where the strong-armed Rodgers was capable of heaving the ball a long distance, usually right into Hite’s arms for another long touchdown.

Hite was also an exceptional runner, eclipsing 100 yards or more in a game four times, including a 180-yard, one-touchdown performance in West Virginia’s 19-0 victory over Virginia Tech in 1915. Hite, not Rodgers, was actually WVU’s top grounder gainer that season with 531 yards on 103 totes. He produced 11 total touchdowns during his three seasons playing for the Mountaineers.

“The University never had a finer athlete,” Rodgers said in 1952 of his WVU teammate. “(Hite) played the game hard and fair and had a desire to win.”

Hite became a noted prep coach and teacher at Washington Irving High in Clarksburg until his death of a heart attack in 1958.

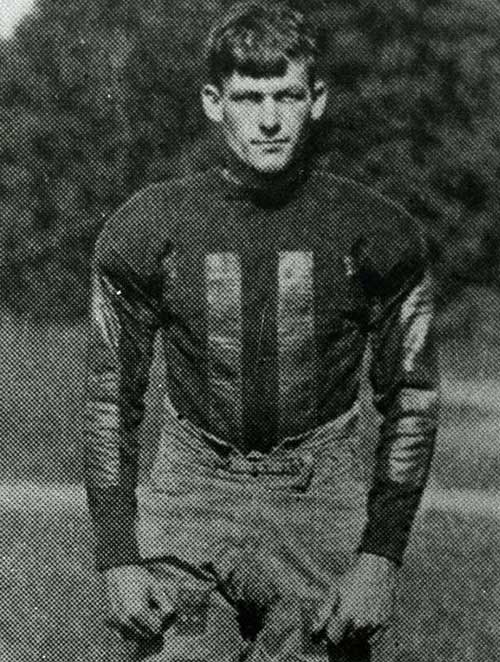

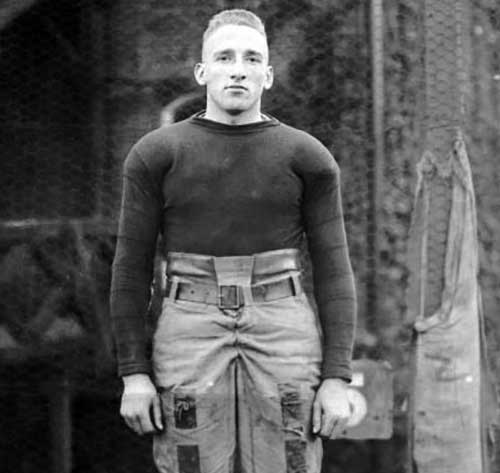

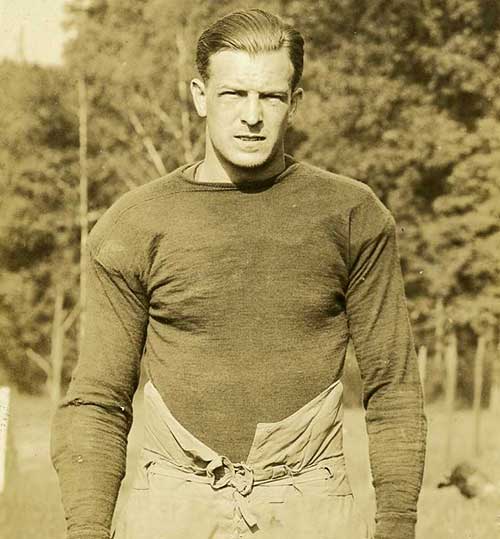

3. Nick Nardacci (HB) 1921-24

In the autumn of 1960, long-time Pittsburgh Press sports editor Chester Smith came up with an intriguing and somewhat controversial listing of West Virginia University’s all-time greatest football players. The vast majority of Smith’s 22-member all-time team are now in the WVU Sports Hall of Fame, including such notables as Ira Errett Rodgers, Russ Bailey, Joe Stydahar, Sam Huff, Bruce Bosley, Fred Wyant, etc.

However, one of Smith’s choices who has since slipped through the cracks was game-breaking Youngstown, Ohio, running back Nick Nardacci (pronounced Nar-duh-CEE).

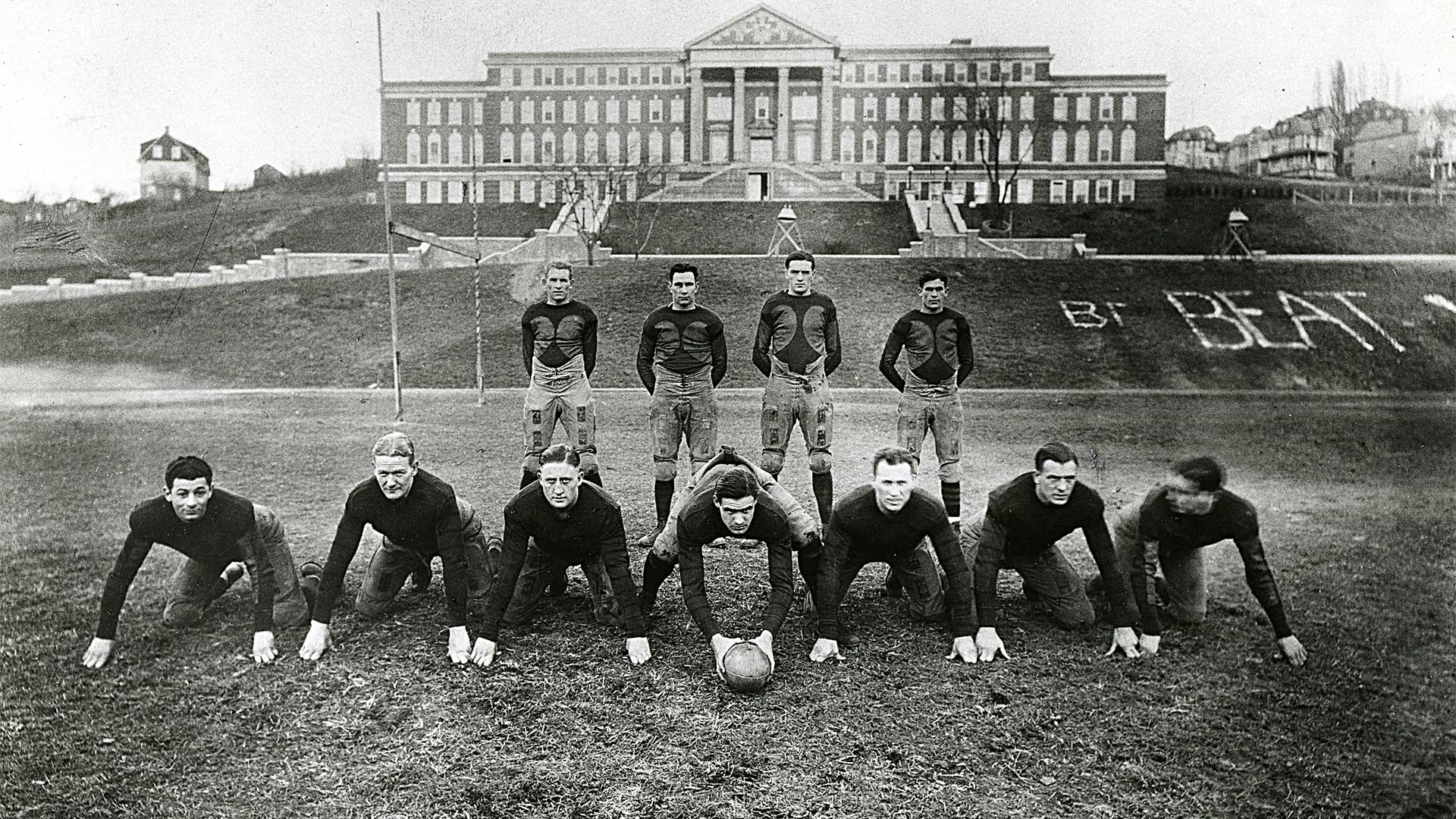

Nardacci was arguably the most elusive player on Dr. Clarence Spears’ great Mountaineer teams of the mid-1920s that won 25 games, lost only two and tied one during a three-year span from 1922-24 considered the most dominant in school history.

“Nick Nardacci was the most difficult to explain,” Smith wrote. “His forte was shiftiness rather than speed. He was never a sitting duck for a tackler and chasing him was like trying to put your finger on a globule of quicksilver.”

Nardacci ran for 123 yards and scored the opening touchdown in West Virginia’s 21-13 victory over Gonzaga in the 1922 East-West Bowl, a mere 26 days after rushing for 153 yards and scoring both touchdowns in West Virginia’s great upset victory over Greasy Neale’s powerful Washington & Jefferson team.

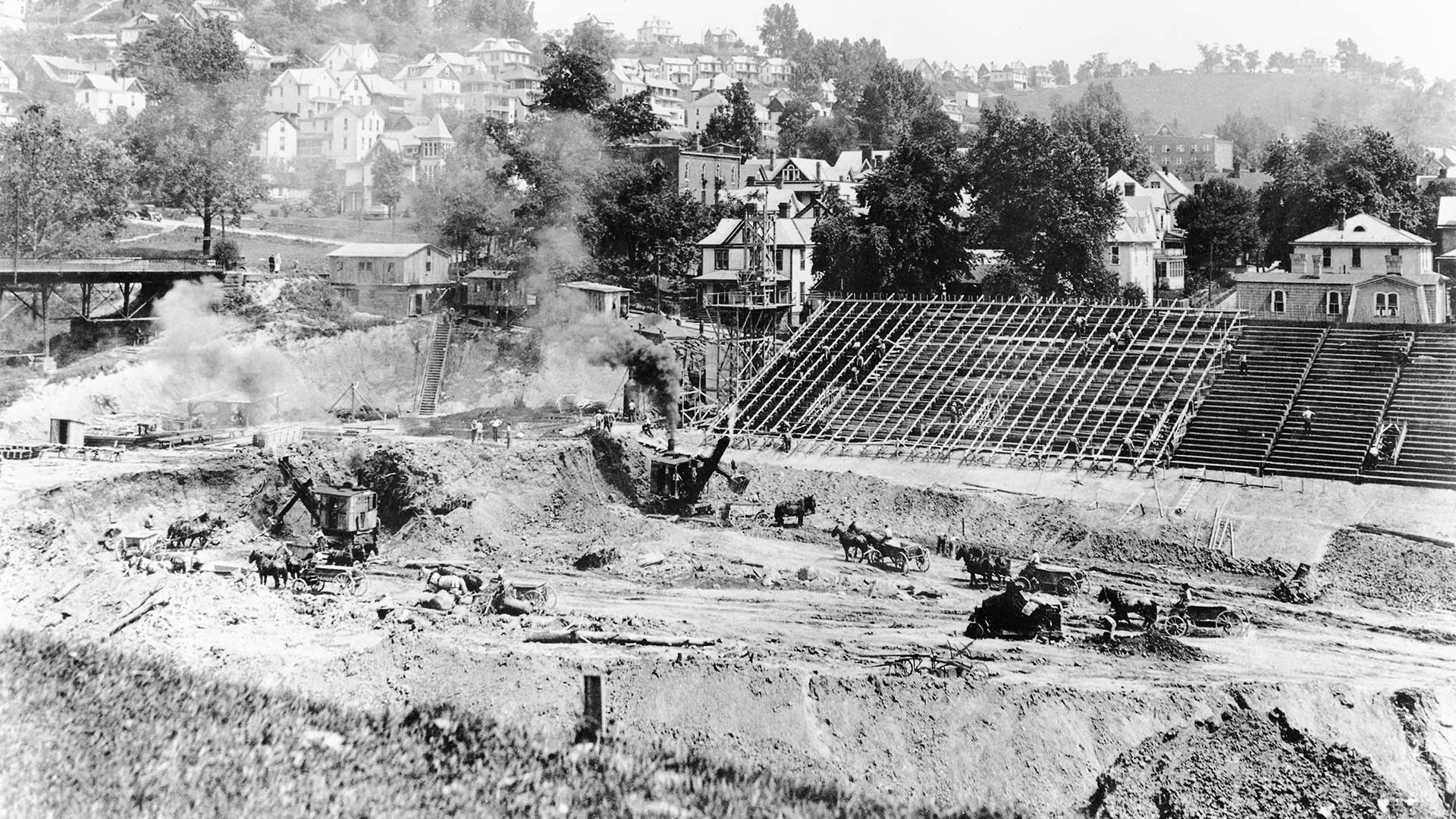

Nardacci was also the offensive catalyst in West Virginia’s amazing 40-7 victory over the Presidents in 1924 in front of nearly 20,000 fans at West Virginia’s old “Splinter Stadium,” where the Mountainlair currently sits. He played great games against Pitt, his two touchdowns the difference in West Virginia’s 13-7 victory over the Pop Warner-led Panthers in 1923 and he was also a contributor in WVU’s great 9-6 upset of Pitt in 1922.

Nardacci, the team’s leading rusher during the 1922 and 1923 seasons, ran for more than 1,600 yards and accounted for 29 touchdowns during his brilliant three-year varsity career. According to the late Tony Constantine, former Morgantown Post sports editor and WVU historian, Nardacci was one of Spears’ favorite players because of his courage and toughness. Constantine once recalled a game at New York’s Polo Grounds in 1923 when the 155-pound Nardacci fought off a cordon of Rutgers blockers to tackle the Knights’ 225-pound All-American fullback Homer Hazel out in the open, a defensive play Spears called “one of the greatest he’d ever seen.”

Nardacci later operated a successful medical practice in Youngstown, Ohio, where he died at age 60 in 1961.

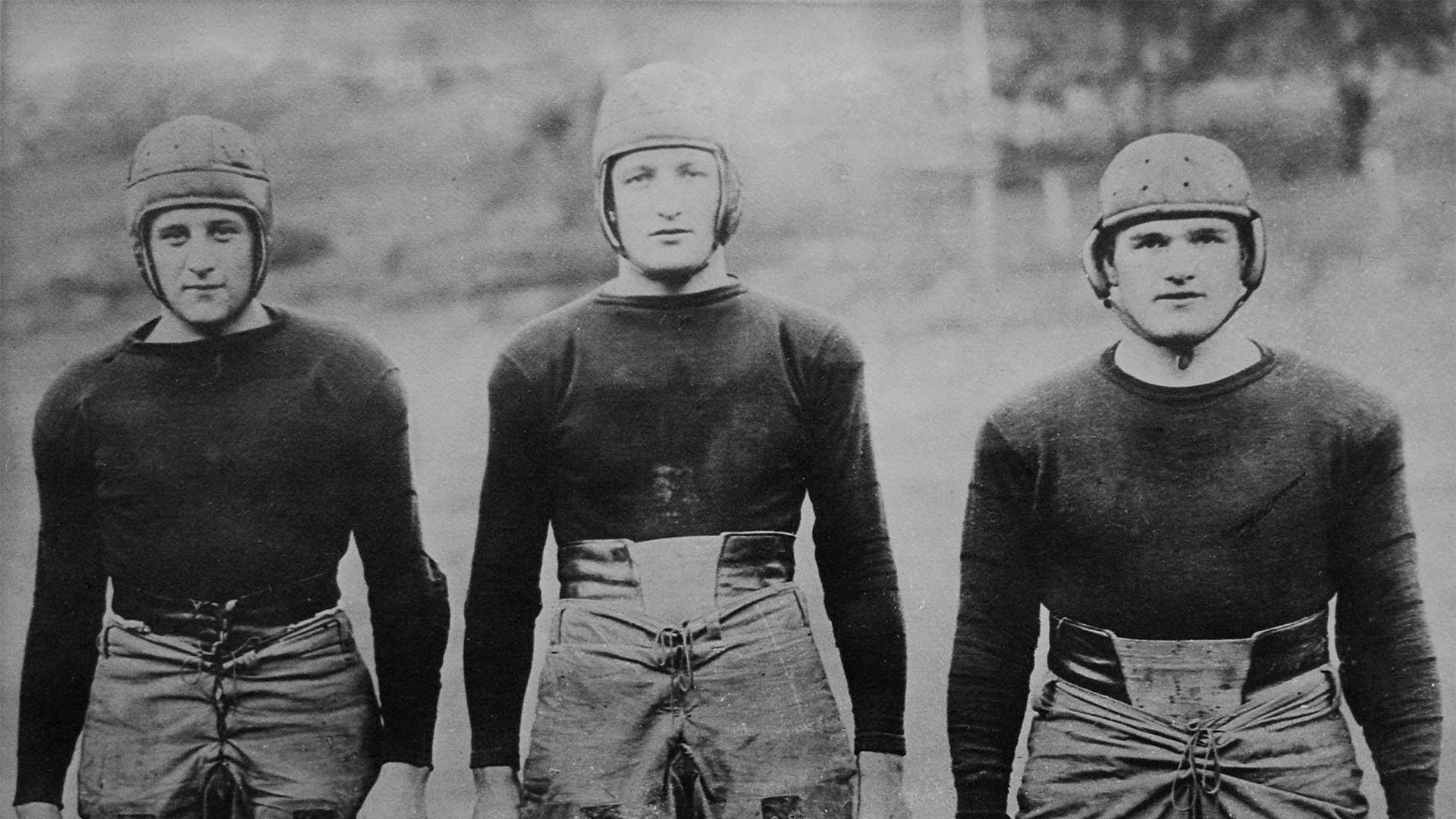

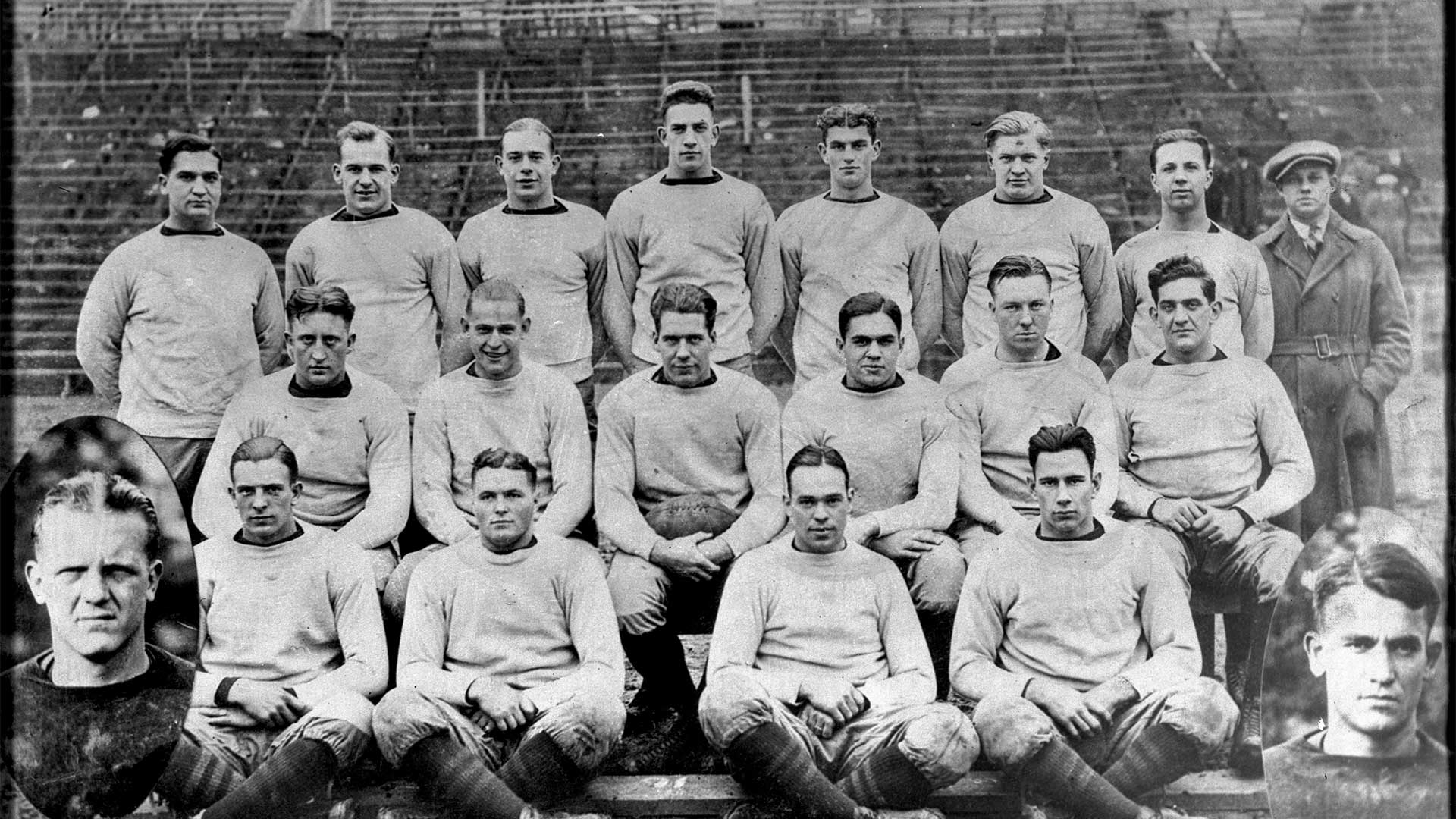

4. Gus Ekberg (FB), 1922-24

Dr. Clarence Spears was the first West Virginia football coach to really scour the country looking for grid talent, and one of his recruiting excursions led him to Minneapolis, Minnesota, to land University of Minnesota fullback Gus Ekberg.

Ekberg was one of the few bright spots on an otherwise moribund Golden Gopher team that won just one of seven games and finished at the bottom of the Western Conference standings before choosing to transfer to a better football school.

Ekberg, standing 5-feet-9 inches, and weighing 180 pounds, considered Penn, Syracuse and Dartmouth before picking West Virginia, where he was paired with Nick Nardacci and Jack Simons in a Mountaineer backfield considered among the best in the East for the 1922 and 1923 seasons.

Ekberg ran for 561 yards and scored six touchdowns as WVU’s primary short-yardage runner in 1922, contributed 454 yards and three scores during an injury-plagued 1923 season, and then returned to good health in 1924 to lead the team with a career-high 612 yards rushing and nine touchdowns.

He ran for a career-high 158 yards in West Virginia’s 1923 revenge victory over a Washington & Lee team that tied the Mountaineers 12-12 in 1922 (the Mountaineers’ lone blemish that season), and Ekberg also topped the 100-yard barrier four other times during an outstanding three-year Mountaineer career.

In 1960, Chester Smith omitted Ekberg from his all-time West Virginia football team, choosing instead to list Parkersburg’s Pete Barnum as his fullback, a pick Tony Constantine later questioned. Constantine wrote, “Gus Ekberg was a better and smarter fullback (than Barnum) in the same era.”

Ekberg played one season of professional football with the Cleveland Bulldogs in 1925, and later spent a season as an assistant coach on Ira Errett Rodgers’s WVU staff before earning his law degree. Ekberg practiced law in Charleston and later back in his home state of Minnesota, where, according to his Wikipedia page, he died at age 54 in 1952.

5. Carl Davis (T) 1923-25

Charleston’s Carl Davis wasn’t big for a tackle, standing 6-feet-1 inches and weighing just 180 pounds, but he sure played much bigger than he appeared by clearing a path for one of college football’s most effective offensive attacks which became known as the “Spears Shift.”

The “Spears Shift,” a version of which Knute Rockne ran at Notre Dame, was predicated on precision, timing, speed and rapid movement right before the ball was snapped requiring quick and agile linemen who were in great shape. Davis, who spent one year at Michigan in 1921 before transferring to WVU, was perfectly suited for Spears’ shift attack.

Davis became a starting left tackle on the 1923 team and helped the Mountaineers to a 7-1-1 record that season. West Virginia averaged 319 yards per game rushing and outscored its opponents 296-41. It was much the same in 1924 when the Mountaineers won eight of nine games, outscored their opponents 282-45 and produced 339.8 yards per game. Davis’ senior year in 1925 saw WVU again win eight of nine games, outscore its opponents by a 175-18 margin, and again average more than 300 yards per game. All three years Davis was a starting tackle West Virginia was considered one of the 10 best teams in college football.

“The late Carl Davis was a coach’s dream,” Smith wrote in 1960.

Davis was the first player in school history to be invited to play in the East-West Shrine All-Star Game played in San Francisco and he later played one year of professional football with the Frankford Yellow Jackets. For years afterward, he became a prominent attorney in his native Charleston until his death in 1959 at age 56.

6. Robert “Pete” Barnum (FB) 1922-23, 1925

Parkersburg’s Robert “Pete” Barnum played a supporting role as a vicious tackler, blocker and field-flipping punter on Clarence Spears’ great 1922-23 Mountaineer teams, sat out the 1924 season to concentrate on academics and then returned to the field in 1925 to lead West Virginia to an outstanding 8-1 record with its lone defeat coming at Pitt.

Barnum, who once scored 19 points at the 1920 West Virginia high school track and field championships by winning the hammer, discus and javelin and finishing second in the shot put, had his best season as a Mountaineer in 1925 when he carried the football 244 times, gaining 761 yards and scoring six touchdowns. Four times that season Barnum gained for more than 100 yards, including a career-high 147 yards in West Virginia’s impressive 20-0 victory at Boston College.

Barnum also topped the 100-yard barrier against Washington & Lee, Washington and Jefferson and Pitt, a 15-7 Mountaineer defeat. Barnum competed 11 passes for 197 yards and a touchdown from his fullback position, and also caught seven career passes, one of those going for a score.

“(Barnum) was a deadly ball carrier on the inside and gave mediocre teams a polish they would not have had otherwise,” Smith wrote in 1960.

Barnum, who also played a little professional football following his WVU career, fell into a vat of molten metal while working at Bethlehem Steel Corp. in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1929 and died a few days later. He was just 27 years old.

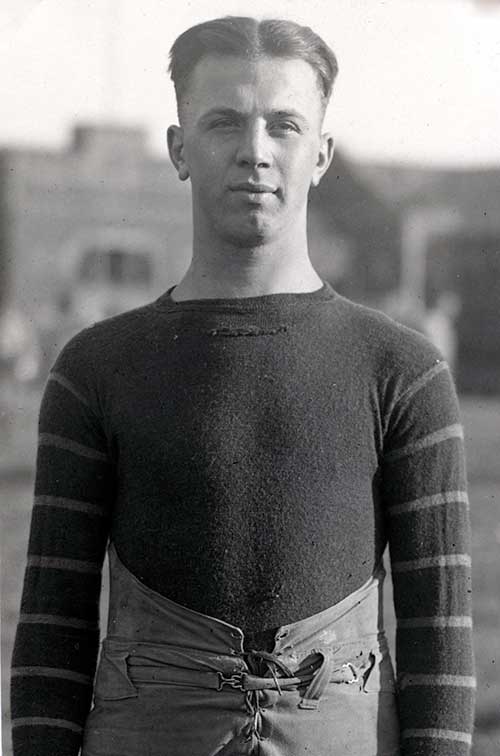

7. Francis “Skeets” Farley (QB) 1924-25

Francis “Skeets” Farley was one of the most accurate passers of his era and one of the key players on West Virginia’s great, nationally-ranked teams of 1924 and 1925.

Throwing a football that more resembled a pumpkin than the prolate spheroid it has become today, Farley completed better than 50 percent of his pass attempts during his senior season in 1925, accounting for almost 600 yards and four touchdowns through the air.

In the 1920s, when passing was usually done as a last resort, a quarterback completing 30 percent of his pass tries was considered acceptable. In his two seasons after transferring from VMI, the Charleston native passed for more than 1,000 yards and 10 touchdowns, he also ran for nearly 900 yards and contributed 14 rushing touchdowns.

His best rushing performance was a 13-carry, 154-yard effort in a home win against Bethany in 1924, and as a defender he established a long-standing school record by intercepting four passes in West Virginia’s 15-7 loss at Pitt in 1925.

What Farley accomplished was even more impressive when considering he weighed just 138 pounds stripped down.

“His wiry 5-10 frame packed, pound for pound, about as much athletic skill as anyone who ever wore a Mountaineer uniform in at least 50 years,” Constantine wrote in 1965. “Skeets rates second only to the immortal Ira Errett Rodgers as a forward passer. He owned a great arm, and he hit his receivers with unerring accuracy.”

Constantine once recalled Farley completing his first “seven or eight passes in a row” in West Virginia’s great 40-7 blowout victory over powerful Washington & Jefferson in 1924.

Farley had a habit of licking his fingers before he was about to throw a pass, often tipping off to the opposition the Mountaineers’ choice of offensive plays. After one game, a Colgate scout came up to Farley afterward and told him that the Raiders knew every time he was about to pass the football.

However, the intelligence did little to stop Farley’s passing that afternoon (163 yards and two touchdowns, including a 52-yarder to Woody Bruder), nor did it keep Colgate from absorbing a 34-2 beating by the Mountaineers.

That’s how good Skeets Farley was as a passer, and that’s how good those Mountaineer teams Farley played on were back then.

Following graduation, Farley served many years as the executive secretary of the West Virginia Petroleum Association while residing in Charleston.

* Note: Statistics referenced in this story were compiled through research of play-by-play accounts from local newspapers.