The professional historians call it counterfactual history, or virtual history, the form of history that attempts to answer the what-if questions that can make up any number of alternative versions of history. For instance, what if Adolph Hitler had been assassinated in July, 1944 instead of committing suicide nearly a year later in 1945?

Would Hitler’s assassination have caused the Germans to surrender earlier than they did, saving countless lives during World War II?

What if JFK had survived his motorcade ride through Dallas on November 22, 1963? Would he have pulled out of Vietnam after the 1964 election as many of his supporters believed he would have?

One of the favorite counterfactual arguments of all-time revolves around the size of Cleopatra’s nose. As the discussion goes, had Cleopatra’s nose been longer, or had she not been as attractive as she was, Julius Caesar and Mark Antony wouldn’t have stayed as long as they did in Egypt, which would have meant an entirely different outlook for the history of the world.

That’s a stretch (pun intended) but, really, how can you know for certain? You can’t because it’s speculative, but nonetheless, counterfactual history can also be a lot of fun.

In the sports realm, would Lou Gehrig have gone on to become one of the all-time Yankee greats had Wally Pipp not shown up to the ballpark with a headache one afternoon?

Probably, but …

What if Lew Alcindor would have picked St. John’s instead of UCLA as his college choice in 1965? John Wooden was a good college coach with one national title under his belt, but would Wooden (then 55 when Alcindor signed with the Bruins) be considered one of the greatest coaches in sports history if Alcindor had remained on the East Coast?

Perhaps, but …

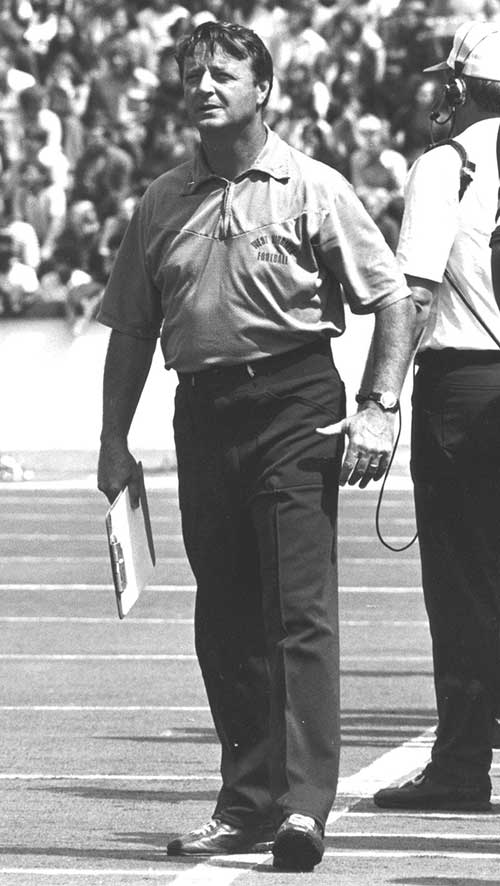

Consider some of the counterfactuals at West Virginia University: What if Bobby Bowden had chosen to stay at WVU in 1976 instead of going to Florida State at a time when Florida was on probation and Miami’s grid program was struggling in the mid-1970s?

Would the personable Bowden have become the hall of fame coach that he was at Florida State if he had remained in Morgantown?

Furthermore, would Florida State have even pulled the trigger on Bowden if Bill McKenzie’s kick sails wide right in the ’75 Pitt game? Keep in mind, Bowden had won less than 60 percent of his college games at WVU prior to the 1975 season.

What would have become of Sam Huff if fortuitous circumstances hadn’t intervened? Huff was going to quit the New York Giants during training camp in his rookie year until line coach Ed Kolman walked into the locker room, discovered Huff packing up his suitcase and convinced him to stick it out.

What if Kolman had decided to stay out on the field a little longer?

Would Huff have become a banker instead of a hall of fame linebacker?

Who would have been West Virginia’s head football coach in 2008 if Bill Stewart hadn’t won the Fiesta Bowl? Would Stew still have gotten the job, or, would it have been Skip Holtz running the show in Morgantown?

You can go on and on with these, but neither time nor space permits that here so I’ve narrowed it down to three of the most interesting what-ifs in Mountaineer football history:

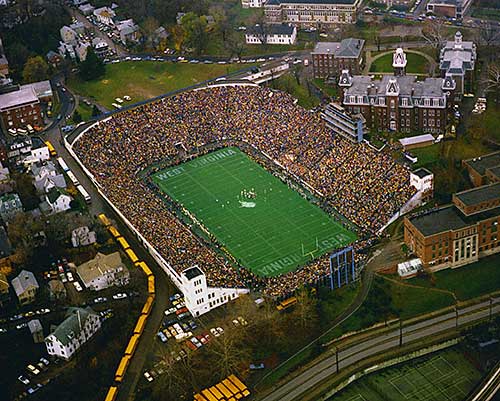

What if old Mountaineer Field had been renovated and expanded instead of being mothballed?

Soon after West Virginia returned to Morgantown following its 13-10 victory over North Carolina State in the 1975 Peach Bowl, athletic director Leland Byrd received an alarming report from the school’s physical plant - Mountaineer Field was falling apart.

Byrd was presented with two options: renovate old Mountaineer Field and add a second deck to increase its capacity to 45,000 or construct a new football stadium in another part of town. Many in Morgantown wanted to renovate the old stadium and keep it on campus, but eventually, the decision was made to construct a new stadium out in Evansdale next to the University hospital and tear down the old one.

What would have happened to Mountaineer football if the old stadium was renovated instead building a new one?

Would Don Nehlen have been West Virginia’s football coach? Would the Mountaineers have vied for two national championships under Nehlen, and another a decade later under Rich Rodriguez?

Would the program have been in a position to get invited, first to the Big East as an all-sport member when the league needed teams to fulfill its new CBS television contract, and then 17 years later to the Big 12 when the Big East imploded?

Here are some clues.

For starters, a big reason the late Dick Martin chose to take the West Virginia AD job in 1979 was because of the school’s decision to construct Mountaineer Field, a clear demonstration of West Virginia’s commitment to having a big-time college football program.

Said Martin in the summer of 2006, “(The new stadium) was one of the reasons I went there. If you could build the stadium that I saw, and within a 200-mile radius having some really outstanding football players as well as an improving road system coming into Morgantown, all of that together made the West Virginia job an interesting one.”

Why was Dick Martin so important in the whole scheme of things? After all, his AD tenure at WVU lasted just two and a half tumultuous years.

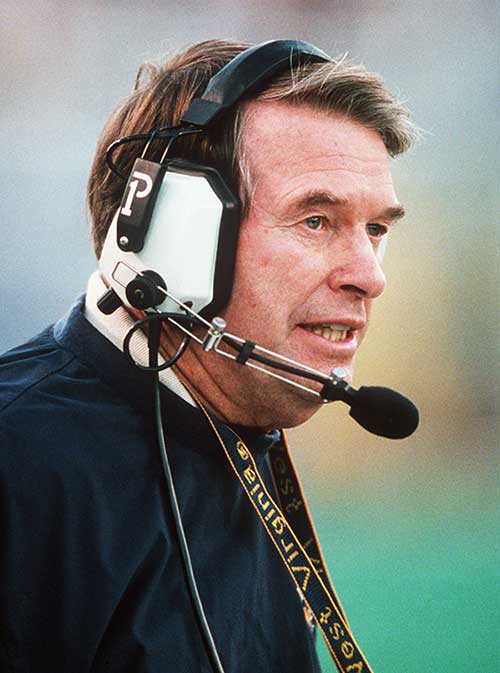

Well, he was the guy who hired Don Nehlen, then an assistant on Bo Schembechler’s Michigan coaching staff.

“(Huntington native) Bob Marcum was the first one to mention Don to me,” Martin recalled. “I was working at the Big Eight office at the time and Bob was the AD at Iowa State and then at Kansas. Bob recommended Don to me and I just kind of did the research from there.”

Keep in mind, Don Nehlen was not a familiar name at all to West Virginians in 1979, and Martin wanted to keep it that way until he could get the search committee and Athletic Council on board with his line of thinking.

Most fans then had their hearts set on Bill Mallory as West Virginia’s next football coach.

“At the time, to protect the overall process to make sure it worked right, you had to be a little more secretive,” Martin said. “Not that I was trying to hide anything, but you can over-blow something and people can get in different camps.”

When Michigan coach Bo Schembechler learned that Martin was pursuing Nehlen, he counseled his assistant to take a pass on the WVU job and wait for a better one to come open.

“He looked at our schedule and he saw Oklahoma on there, he saw Penn State and he saw Pitt and he said, ‘Don, you’ve got about four, five or six losses on here right away. Every coach that’s ever coached there if they win they leave and if they lose they get fired. I just think it’s a big mistake,’” Nehlen once recalled. “You’re making good money and we go to the Rose Bowl every year, in two or three years I’ll get you a good job.”

But Nehlen saw something different at West Virginia - a school and fan base dying to have a respectable football program that was located not too far away from some of the best high school football players in the country.

Nehlen also viewed the construction of the new stadium as a clear demonstration of the school’s commitment to fielding a big-time college football program.

“I took a map and drew a circle around Morgantown,” Nehlen said. “I said to Bo, ‘There are a ton of football players within 300 miles of Morgantown. I got a feeling I can get me 15 of those guys a year.”

Had West Virginia chosen instead to renovate old Mountaineer Field that likely would have meant no Dick Martin, which would have meant no Don Nehlen, which would have meant no Flying WV logo, no Jeff Hostetler, no Major Harris, no run at national titles in 1989 and 1993, no Rich Rodriguez, and, quite possibly, exclusion from one of the Power Five conferences today.

Bobby Bowden once recalled the state of West Virginia’s football program when he was hired by Jim Carlen to run the Mountaineer offense in 1966.

“When we got there in the mid-1960s, it was kind of like North Carolina and Duke with their basketball,” Bowden said. “When Jim went up there he kind of changed that. He got them a little bit more involved in football. Then, when we got out of the Southern Conference where we had people we could beat, my gosh, we started playing SMU, Stanford, California and those schools and we began spreading it around a little bit.

“But Don did an amazing job,” Bowden continued. “No. 1, he had that Michigan background. He used to coach at Michigan when he was an assistant coach and he was used to being big-time all the way, so when he comes to West Virginia, he just assumes he’s going to do the same thing here. He changed the uniforms to even look like Michigan.”

Said Bowden on another occasion, “I think Don Nehlen put West Virginia on the modern map. Sam Huff, Bruce Bosley, Freddy Wyant and all those guys that played back in the 1950s, they put West Virginia on the map, but then it seemed like Don Nehlen put the modern West Virginia on the map.”

Indeed, he did.

And it wouldn’t have happened without some forward-thinking West Virginians back in the mid-1970s.

“I took a map and drew a circle around Morgantown. I said to Bo, ‘There are a ton of football players within 300 miles of Morgantown. I got a feeling I can get me 15 of those guys a year.”

Don Nehlen

What if Major Harris hadn’t injured his shoulder on the third play of the 1989 Fiesta Bowl?

In 1988, West Virginia rolled through everybody - bad teams, average teams, good teams, really good teams, it didn’t matter - the Mountaineers scored almost at will that year against everyone they faced.

This team was five years in the making, coach Don Nehlen patiently sticking to his plan of redshirting first-year players and developing them through his strength program. By 1988, he had a powerful, experienced offensive line with five seniors up front and a second five as good as most people’s first five, three quality tailbacks, some game-breaking wide receivers, a pair of reliable tight ends and Major Harris, a dynamic, ahead-of-his-time quarterback.

The ’88 team never trailed at halftime of any game it played during the regular season, beat rivals Pitt, Penn State, Maryland, Virginia Tech, Boston College and Syracuse by a combined score of 249-102, including putting 51 points on the scoreboard against Joe Paterno (the most points any Paterno-coached Penn State team had ever surrendered) and averaged nearly 43 points and 500 yards per game during the regular season.

No one could stop this offense - that is until Notre Dame linebacker Michael Stonebreaker slammed Harris to the turf on the third play of the 1989 Sunkist Fiesta Bowl, the de facto college football championship game that season.

Why Harris’ injury was so devastating to West Virginia was because the entire offensive game plan for the national championship game was on his shoulders. Harris didn’t win the Heisman Trophy that year, but he was considered one of game’s most dynamic players, passing for almost 2,000 yards and 14 touchdowns, rushing for 610 more with six TDs and averaging almost eight yards every time he touched the football.

And the 1989 Fiesta Bowl was to be Harris’s showcase game on a national stage.

“Major was so durable, he never got a bump all season and we decided to put a lot of stuff in for him that Notre Dame had never seen,” Nehlen once recalled. “We had some great stuff we worked on and lo and behold, the third play of the game Major comes off the field and he says, ‘Coach, I don’t think I can throw.’ I’m thinking, ‘Oh brother, what did I do to deserve this?’”

“When Major hurt his shoulder it changed everything,” fullback Craig Taylor said a few years ago. “He was done. I heard him in the huddle (complaining about his shoulder) and he never did anything like that before so we knew he was hurt pretty bad.”

Unfortunately, Harris wasn’t the only Mountaineer player injured.

“We go into the game and my left guard Bobby Kovach goes down. Then my right guard John Stroia goes down. Then Major goes down,” Nehlen said. “We couldn’t afford to play Notre Dame with four starters out of the game, but I think we could have gotten by had Major not been hurt.”

Would a healthy Major Harris have been enough to beat the Irish?

Perhaps, but another key injury on the other side of the ball was just as costly. And it happened during the regular season finale when starting safety Darrell Whitmore broke his leg in West Virginia’s 31-10 victory over Syracuse.

Whitmore’s injury forced West Virginia to change everything around in the secondary, putting some key players in unfamiliar spots and that opened up areas Notre Dame quarterback Tony Rice, speedy wide receiver Raghib “Rocket” Ismail, talented flanker Ricky Watters and massive tight end Derek Brown were able to exploit.

Nehlen also thought he did a poor job of handling the distractions that came with playing in college football’s biggest game of the year.

“Notre Dame had been there a lot of times and the media was overwhelming with me,” he said. “I couldn’t move that week and they just drove me crazy. I was not smart enough to say, ‘Hey, I’ve got a team to prepare.’ I got caught up into a mess where I got too involved with the media - and our kids were caught up in the media.”

Had Harris remained healthy, the game likely would have been a shootout, one the Mountaineers could have better managed with Harris running the option and controlling the clock to better protect the defense.

But that wasn’t possible after the third play of the game.

“I would bet my life we would have won that football game,” Nehlen said. “You look at all of the comparative scores: we beat Penn State a lot worse than they did, we beat Pitt a lot worse than they did and I felt we were the better football team, but it was just one of those things. It didn’t work out for us.”

It didn’t, but it possibly could have.

Box Score

| Team | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Notre Dame | 9 | 14 | 3 | 8 | 34 |

| West Virginia | 0 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 21 |

| Qtr | Time | Scoring Play | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10:25 | ND - Hacket 45 yd FG, 7-37 3:00 | 0-3 |

| 1 | 4:34 | ND - A. Johnson 1 yd rush TD (Rush by Graham Fail), 10-61 4:20 | 0-9 |

| 2 | 9:41 | ND - R. Culver 5 yd rush TD (Kick by Ho Good), 11-84 5:07 | 0-16 |

| 2 | 6:18 | WVU - Charlie Baumann 29 yd FG, 11-52 3:23 | 3-16 |

| 2 | 1:48 | ND - Ismail 29 yd TD pass from Rice (Kick by Ho Good), 8-63 4:30 | 3-23 |

| 2 | 0:00 | WVU - Charlie Baumann 31 yd FG, 9-69 1:48 | 6-23 |

| 3 | 5:34 | ND - Ho 32 yd FG, 7-50 3:35 | 6-26 |

| 3 | 3:32 | WVU - Grantis Bell 17 yd TD pass from Major Harris (Kick by Charlie Baumann Good), 7-74 2:02 | 13-26 |

| 4 | 13:05 | ND - Jacobs 3 yd rush TD (Rush by Rice Good), 7-80 3:07 | 13-34 |

| 4 | 1:14 | WVU - Reggie Rembert 3 yd rush TD (Pass by Reggie Rembert Good), 11-59 2:57 | 21-34 |

"When Major hurt his shoulder it changed everything. He was done. I heard him in the huddle (complaining about his shoulder) and he never did anything like that before so we knew he was hurt pretty bad.”

Fullback Craig Taylor

W hat if West Virginia had won the 2007 Backyard Brawl?

West Virginia’s 13-9 loss to Pitt in Morgantown in 2007 still defies logic nine years later. How could a team as good as West Virginia was that year lose to a team as bad as Pitt was?

Aside from its typical loss at South Florida, the Mountaineers steamrolled through their schedule: 62-24 versus Western Michigan, 48-23 over in-state rival Marshall, 31-14 over Maryland, 48-7 against East Carolina, 55-14 versus Syracuse, 38-13 over Mississippi State, 31-3 over Rutgers, 38-31 versus Louisville, 28-23 against Cincinnati and 66-21 over UConn.

The Connecticut win was particularly impressive, West Virginia’s ground game churning out 517 yards in 45-point rout over the 20th-ranked Huskies. It was a terrific performance in every aspect - and against a pretty good UConn team that had lost just twice prior heading into the game.

A week later, not a single one of the 60,100 who attended the 100th version of the Backyard Brawl in Morgantown - including Pitt’s paid cheerleader Bill Hillgrove - could conceive of a way for the 4-7 Panthers to come out victorious.

But it happened.

And it turned college football upside down.

For the first time in school history, the Mountaineers reached No. 1 in the coaches’ poll that week and were No. 2 in the Associated Press poll, meaning a victory over the Panthers would have guaranteed West Virginia a place in the BCS championship game.

Now nine years later, 2007 has since been referred to as the Year of the Upset, beginning with Michigan’s stunning 34-32 loss to Appalachian State to begin the season and continuing throughout until the Panthers beat the Mountaineers on December 1. Fifty-nine times an unranked or lower ranked team defeated a higher ranked team, including a record-setting 13 times when an unranked team knocked off a top-five foe.

The position in the polls hardest hit was college football’s No. 2 team, a victim seven times to upset losses, including the most stunning one of all when No. 2 West Virginia lost to unranked Pitt on the final weekend of the season.

If West Virginia hadn’t lost to Pitt was the school’s first national football championship a possibility?

Heading into the final week of the season, West Virginia was second to Missouri in the BCS standings. The Tigers were good but not overwhelmingly good, as proven by Oklahoma’s blowout victory over the Tigers in the 2007 Big 12 Championship game.

That knocked Missouri out of the national championship picture.

After West Virginia, the next team in line in the BCS standings was Ohio State. Again, the Buckeyes were very good but not invincible, as proven by their 28-21 home loss to unranked Illinois in early November.

Therefore, a West Virginia-Ohio State matchup in New Orleans on January 7 for the national championship was the expected outcome leading up to West Virginia’s 7:45 p.m. kickoff against Pitt.

Then, three and a half hours later, that obviously changed.

“There were three great teams that year in college football - Ohio State, Southern Cal and Oklahoma,” West Virginia defensive line coach Bill Kirelawich recalled. “Nobody wanted to play Southern Cal or Oklahoma. You wanted to play Ohio State because they were the weakest of the three. So we lose to Pitt and we ended up playing Oklahoma in the Fiesta Bowl and I’m thinking to myself, ‘We’re going to get murdered.’ You didn’t want those guys.”

The Fiesta Bowl was a blowout - but not the way Kirelawich or almost everyone else expected: West Virginia routed Oklahoma 48-28, the same Sooner team that knocked Missouri out of the national championship picture in the Big 12 championship game.

As for the BCS championship game, a two-loss LSU team jumped five places in the BCS standings from No. 7 to No. 2 to face top-ranked Ohio State in the title game.

And those same Buckeyes that West Virginia was going to face in the championship game proved to be no match for the Tigers, LSU winning easily 38-24.

Clearly, the Mountaineers’ first national football title was there for the taking, but it slipped out their hands on that miserable December night in Morgantown.

And it remains the biggest what-if in school history.

Week 13 BCS Standings (11/25)

| Rank | Team | Record |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Missouri | 11-1 |

| 2. | West Virginia | 10-1 |

| 3. | Ohio State | 11-1 |

| 4. | Georgia | 10-2 |

| 5. | Kansas | 11-1 |

| 6. | Virginia Tech | 10-2 |

| 7. | LSU | 10-2 |

| 8. | USC | 9-2 |

| 9. | Oklahoma | 10-2 |

| 10. | Florida | 9-3 |

"There were three great teams that year in college football - Ohio State, Southern Cal and Oklahoma. Nobody wanted to play Southern Cal or Oklahoma. You wanted to play Ohio State because they were the weakest of the three. So we lose to Pitt and we ended up playing Oklahoma in the Fiesta Bowl and I’m thinking to myself, ‘We’re going to get murdered.’ You didn’t want those guys.””

Defensive Line coach Bill Kirelawich